Jump through time at Ferrara’s newly opened Museum of Italian Judaism

FERRARA, Italy — Some 2,000 years ago, a girl named Aster lived in Jerusalem. She was very young when the city fell at the hands of the Romans and was deported to Rome as a slave.

“Claudia Aster, captiva ierosolimitana,” or, “Claudia Aster, prisoner from Jerusalem,” reads her gravemarker, one of the 200 objects displayed in the exhibit, “Jews, An Italian Story: The First Thousand Years.” It is the first piece of the permanent exhibition of the Museo dell’Ebraismo Italiano e della Shoah (Museum of Italian Judaism and the Holocaust), or MEIS, inaugurated a few months ago in the northern Italian city of Ferrara.

Aster’s story, in the section about Jews and Rome, is brought to life alongside that of the thousands of Jews who lost their homeland and freedom in the Holy Land, forced to find a new identity in the Eternal City.

Visitors experience her loss as they enter a narrow room, which opens with a simple animated installation: a wall of golden Jerusalem stone is burning, the flames dancing under a serene starry sky.

Late 1st century epitaph for Claudia Aster, on loan at MEIS from Museo Archeologico nazionale, Naples. Courtesy/ Museo Archeologico nazionale, Naples)

Visitors then go through a passage featuring the decorations of the Arch of Titus, symbol of the Jewish defeat, and find themselves in front of a map of the Colosseum, the monumental amphitheater built by exploiting the treasures sacked in Jerusalem and the labor of Jewish slaves. A relief of the Arch (a plaster reproduction from the ’30s) shows the spoils of the Temple.

MEIS director Simonetta Della Seta says the rooms are designed to be “immersive.” It’s a good description of a visit to the museum overall — a journey through time and space that succeeds in getting the point across. In this museum’s narrative, if the story of the Jewish people started in the Middle East, Italy came next.

Della Seta is a 60-year-old former academic, Middle East correspondent, and cultural attaché at the Italian embassy in Tel Aviv, who was appointed the new museum’s director in 2016.

Della Seta met with The Times of Israel on a scorching, muggy July day all too typical of the region. But despite the heat, the city radiated with all the historical beauty that has earned its designation as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

In the storied city, the MEIS building itself has a tale to tell: it is a former prison where the fascists locked up Jewish prisoners during the Holocaust before sending them to the death camps. Several years ago the city of Ferrara freed up the building, which was deemed an ideal site for the museum because of its history.

The city center is only a few minutes away, with its magnificent medieval municipal square and cathedral. Behind lie the streets of the former ghetto, still lined with brick and brightly colored buildings. The structures boast beautiful terra cotta cornices and flowers at the windows –they are a perfect living postcard of Italian small town life.

Today the Jewish community of Ferrara numbers a few dozen people, though at its height in 1800 the city boasted a Jewish population of 2,000, according to leading demographer Prof. Sergio Della Pergola.

One building accommodating three of the city’s synagogues, which date back between the 15th and 17th centuries, is under renovation after the city’s 2012 earthquake.

“Ferrara has had a continuous Jewish presence for the past 1,000 years,” Della Seta said, highlighting how this rich history and heritage have been an important factor in choosing the museum’s location.

The 47 million euro ($55.1 million) museum was established through a new law, and the costs were fully covered by the Ministry of Cultural Heritage.

At the MEIS, in addition to the exhibit “Jews, An Italian Story,” visitors can already enjoy the Giardino delle Domande (Garden of Questions), an outdoor maze where finding the right path requires answering questions about kosher dietary laws.

The rest of the site is still under construction. The final complex, set to open in another three years, will include five new buildings plus two preexisting ones, and will feature a library, an auditorium, a kosher restaurant, a café, and a museum for children.

“The goal is to complete everything by 2021,” Della Seta said, emphasizing how important it has been to start working on the content.

“We had to ask ourselves how to create our exhibition, considering that we don’t have a collection, nor do we own any artifacts,” said Della Seta.

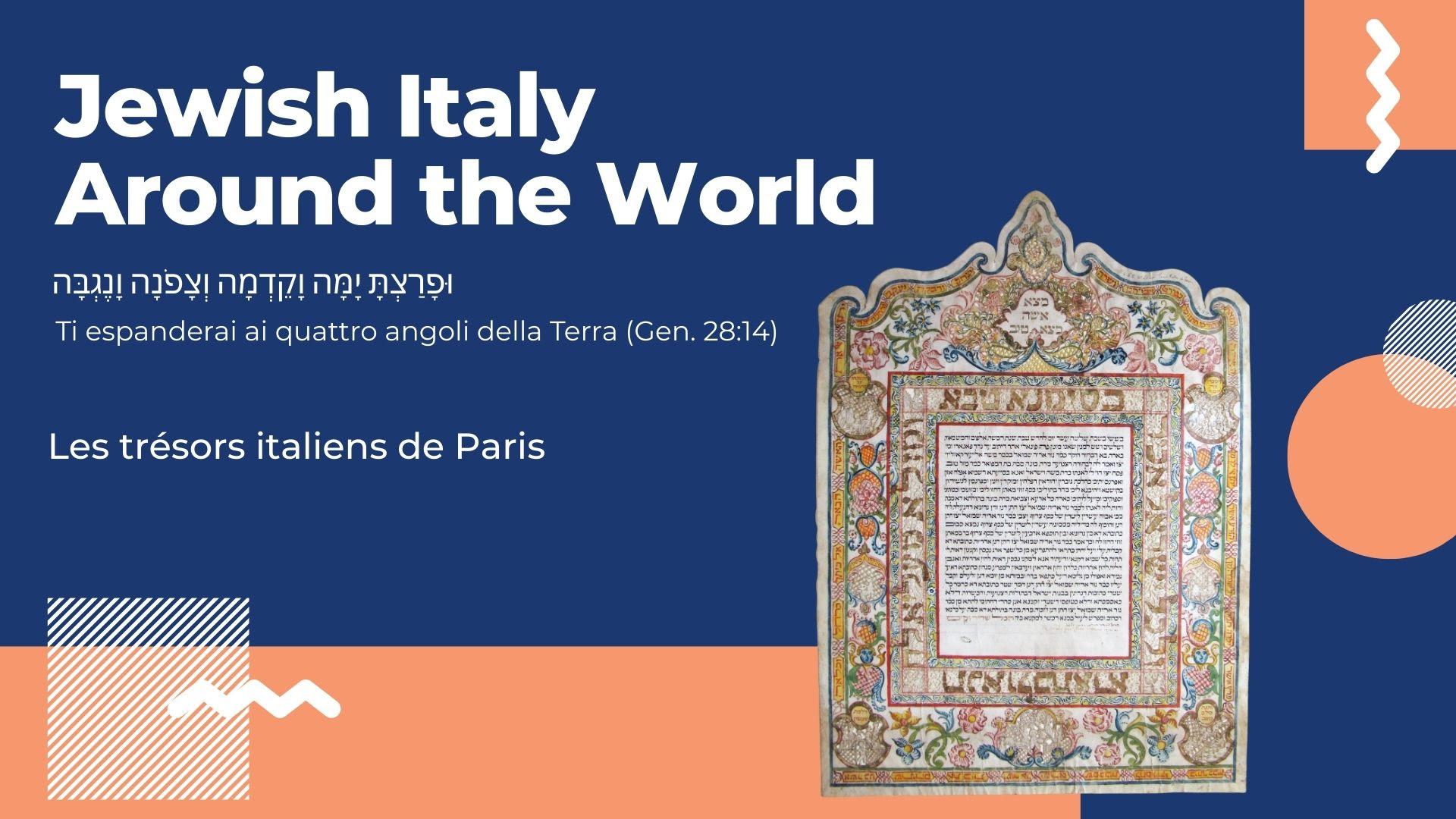

“From my perspective, this has been an advantage, because we focused on building the narrative, the itinerary, and only after did we work on finding the suitable objects, which have arrived on loan from museums all over Italy and all over the world,” she said.

Room after room, the narrative takes shape through maps, objects, excerpts of Jewish and non-Jewish texts, and multimedia installations featuring videos of historians and experts — among whom are the three curators Anna Foa, Giancarlo Lacerenza, and Daniele Jalla.

Visitors encounter Abraham’s journey, the Roman period, the relationship between Jews and the first Christians, figures like Obadiah the Proselyte (Ovadyah ha-Ger), a young cleric in Apulia who converted to Judaism and is the composer of the oldest transcriptions of synagogal music ever discovered, or Shabbethai Donnolo, the mystic and scientist.

The richness of Jewish life in the Roman Empire is conveyed by a striking reproduction of some of the most beautiful chambers of the Rome’s Jewish catacombs. Eleven funerary stones are displayed to mark the existence of at least 11 Jewish functioning congregations in the city.

The Roman tombstones, inscribed with Jewish symbols such as menorahs and citrons, are all written in Greek. It was southern Italy that was the home of the Hebrew language’s revival and hundreds of years of thriving Jewish life.

Until the expulsion of the Jews from Spanish domains starting in 1492, flourishing communities blossomed in Campania, Sicily, Apulia, and Calabria, where culture, sciences, and commerce prospered with them.

At its zenith just after the Spanish expulsions, the Italian Jewish community numbered 50,000 — but this was short-lived. Soon after the influx of thousands of Jews from Spain, the Jewish community of southern Italy was forced to flee as well, said demographer Della Pergola.

The Jewish traveler Beniamino da Tudela, or, as he is known in Hebrew, Benjamin Metudela, chronicled his journey from Spain to the Holy Land between 1159 and 1173 in his book “Sefer Massa’ot,” meaning, “The Book of Travels.”

“In Salerno, where the Christians have a school of medicine, about 600 Jews live,” wrote.

At the museum, Metudela’s descriptions of the many Italian communities he visited are interwoven in an animated slideshow with engaging drawings of the Italian Jewish illustrator Emanuele Luzzati (1921-2007), leading the audience in a metaphoric dance around the Italian peninsula.

The full scope of what the Jewish presence has meant for the country is conveyed by a map that documents the hundreds of Jewish settlements that have existed in Italy. There is no region, and hardly any province, that has not known a Jewish community at some point over the course of Italian history.

Today, there are roughly 29,000 Jews living in Italy — about 16,000 less than the 45,000 that called the peninsula home before the Holocaust, said Della Pergola.

“After I was appointed, I spent a few months asking people questions: ‘What is the meaning of a public national museum about Jews in Italy? Why and how can it be relevant for the Italian society at large?’” Della Seta recalled.

“Some answers I received have stayed with me. For example, that Jews have been the first to experience carrying multiple identities, the first to put such emphasis on culture, that they are a minority that has lived for 2,000 years among a majority,” she said.

“In my view, spreading knowledge about Judaism and the Italian Jewish life and history is our primary purpose, but promoting awareness of an experienced identity that has something to teach about the challenges of the contemporary world is also part of what we are doing. It was not by chance that the president of the Italian Republic Sergio Mattarella attended our inauguration,” said Della Seta.

The MEIS so far has been visited by 15,000 people — from Italy, but also Europe and Israel. The museum has signed a document of cooperation with the Ministry of Education to promote visits from schools.

The next section has a slated inaugurated of March 2019 and will focus on the Renaissance. After that, the plan is to cover the time of the ghettos, the age of Emancipation, the 18th and 19th centuries, and contemporary life.

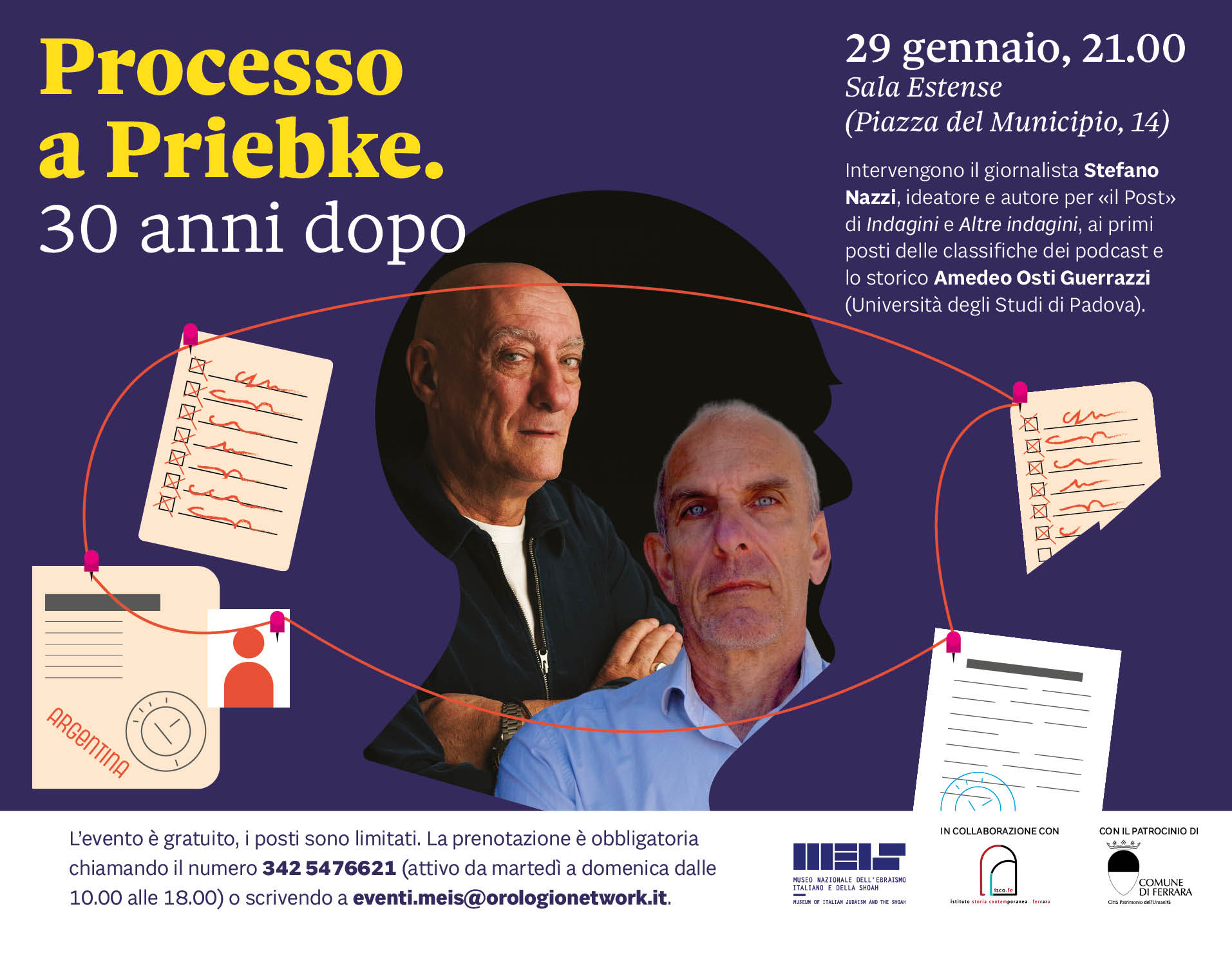

“We are also already working on the part about the Holocaust,” said Della Seta.

“Our goal is to create a place devoted not only to general learning about the Shoah in Italy, but especially to reckoning with history and with questions that have not been dealt with enough: Who were the Italians that replaced the Jews fired from their jobs? Who the ones who took advantage of the situation?” she said.

“I consider myself very lucky to have the opportunity to contribute to shaping such a great cultural institution and spreading knowledge, which in my opinion is the best weapon against anti-Semitism,” Della Seta concluded. “For me, this work is a mission.”

Altri contenuti

12 febbraio, evento online

Giorno della Memoria 2026, il calendario degli eventi

Giorno della Memoria 2026, il programma per le scuole

Viaggio alla scoperta del Salento ebraico