Italian Jews: Rome, the Renaissance and Beyond

MOMENT MAGAZINE

by Carlin Romano

For most Americans familiar with Italian Jewry, the images that linger come from Vittorio De Sica’s evocative 1971 film, The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, the Academy Award-winning picture based on Italian writer Giorgio Bassani’s prize-winning 1962 novel. Set in Bassini’s picturesque hometown of Ferrara, Garden mixed the beauty of provincial Italy, and the allure of gorgeous young people at ease, with a slowly mounting anxiety—the creeping horror by which Italy in 1938 turned on its Jews, and captured, killed or deported some 9,000 of them.

De Sica portrayed the wealthy and aristocratic sister and brother Micol and Alberto Finzi-Contini in their tennis whites, largely ignoring changing times amid the majestic poplars of their lush estate. They invited newly restricted middle-class Jewish friends to party behind their high stone walls, capturing the turning point at which Italy’s assimilated Jews became outcasts.

Now Ferrara, a beguiling small city located on the misty plains of Emilia-Romagna, about 55 miles southwest of Venice, is home to a new museum—the National Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah (Museo Nazionale dell’Ebraismo Italiano e della Shoah) or MEIS. Opened just two years ago in the former two-story brick prison at Via Piangipane 82 where Bassini was once incarcerated by the Fascists, the museum drew some 50,000 visitors last year.

The museum came to Ferrara in a circuitous way. In 2000, the Italian government joined the United Nations and several other countries in establishing January 27 as International Holocaust Remembrance Day. In April 2003, Parliament funded, to the tune of some 47 million euros, the creation of an Italian Holocaust Museum, originally slated for Rome. Subsequent discussions within the government and with the Union of Italian Jewish Communities convinced officials that their vision of a Holocaust museum was too narrow. They then decided that the museum, while paying special attention to the Holocaust, should tell the entire story of Jews in Italy. In December 2006, Parliament amended the 2003 law, creating a national museum. When the then mayor of Rome determined that his city would be better off with a municipal Shoah museum, officials decided to build the museum in Ferrara, a city in which Jews had once prospered.

“THE GOAL,” SAYS MUSEUM DIRECTOR DELLA SETA, “IS TO TELL THE STORY OF SUCH A LONG AND CONTINUOUS RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN A MINORITY AND A MAJORITY. YOU’RE SENDING A MESSAGE TO THE PRESENT THAT DIALOGUE IS POSSIBLE”

“We are not a Jewish museum,” says MEIS’s director, Simonetta Della Seta. “It’s important for me to say this. We are an Italian national museum dealing with the Jewish experience….We have a mission by statute, which is spreading the knowledge of the experience of the Italian Jews for 2,200 years.” The goal, she adds, is to “tell the story of such a long and continuous relationship between a minority and a majority. You’re actually sending a message to the present that dialogue is possible. And this is very important in Europe today.”

Della Seta, who is Jewish, studied at Rome’s La Sapienza university and earned an MA from Brandeis on a Fulbright and a joint PhD from Brandeis and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, writing on contemporary Italian Judaism. After working for a time as a journalist, she became a diplomat, serving as senior adviser to the Italian ambassador to Israel. With her short-cropped hair, bright red-framed glasses and no-nonsense insistence on accuracy in everything the museum does, Della Seta makes it clear that Italian Fascism, and the city’s famed chronicler, Bassani, will never constitute her museum’s marquee story. “The museum is located in Ferrara,” she says. “Giorgio Bassani was a Jew who was born here. He was a great writer. Of course, there has to be a relationship between the museum and Bassani. But Ferrara had other important Jews, like Isaac Lampronti, a 16th-century rabbi who wrote an anthology of the Talmud that’s still in use.” Thus her task is to acknowledge the influence of Bassani’s fictional portrayal of the city without allowing it to dominate the museum’s official mission and obscure the centuries during which Jews flourished there and influenced the country’s culture.

Off the beaten track for most American tourists despite being just a 30-minute train ride from popular Bologna, Ferarra is a UNESCO World Heritage Site famous for its medieval and Renaissance architecture. At its center, dominating every vista, lies the magnificent medieval Castello Estense, the towered and turreted brick fortress of the House of Este, which ruled Ferrara from 1240 to 1598. Ercole d’Este (1431-1505) welcomed Sephardic Jews expelled from Iberia and left the city a remarkable array of palaces, gardens and grand avenues, as well as medieval walls and a Jewish quarter (which became the ghetto in 1624 after the Vatican seized power from the House of Este). The residence of such giants of Italian history as Lucrezia Borgia, Girolamo Savonarola and film director Michelangelo Antonioni, Ferrara punches above its weight for a city with a population now of just 132,000. Indeed, historic bars such as al Brindisi, once frequented by a clientele that included Titian and Cellini (Copernicus lived upstairs), bespeak the glorious times that MEIS itself wishes to recall.

At the moment, the museum is located in two of the restored and modernized buildings of the Ferrara prison, built in 1912 and shuttered in 1992. Plans call for the addition of five new glass buildings on the site, designed to represent the five books of the Torah. When all construction is completed by 2021, the entrance to the museum, which now faces the inner city, will switch to the other side, looking out toward the river that runs through the city.

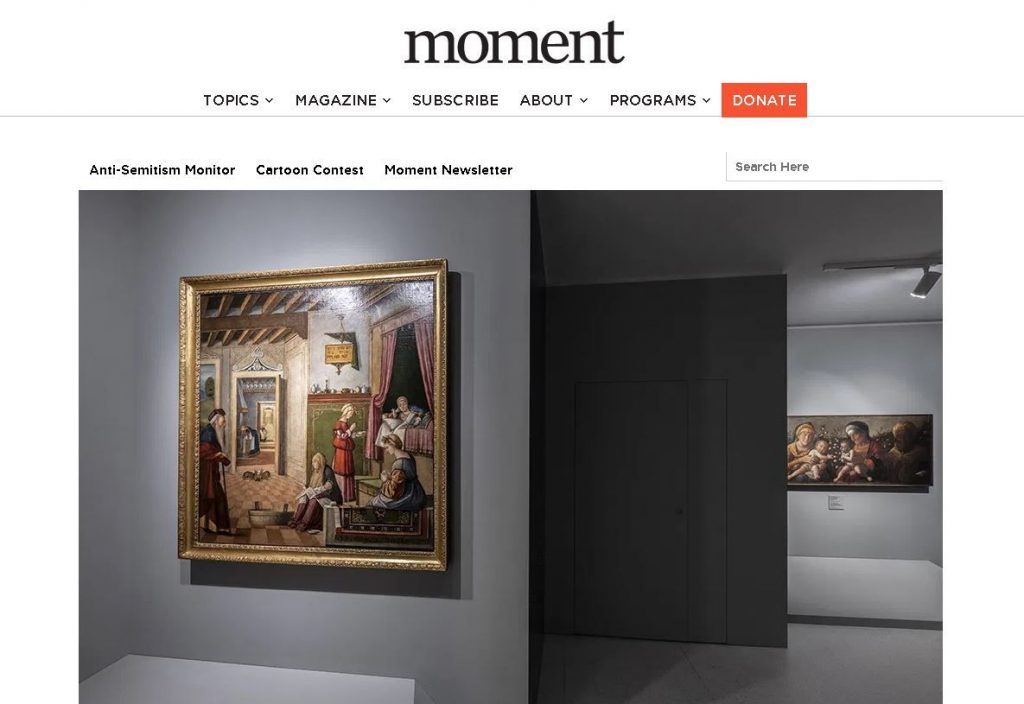

Two exhibitions are currently on view in the main building. On the second floor, “Jews, an Italian Story: The First 1,000 Years,” offers a condensed and permanent version of the museum’s inaugural exhibition. Jews lived in Rome and southern Italy even before Titus conquered Jerusalem in 70 CE and took thousands of Jewish prisoners back to Rome. The exhibition details their history, showcasing more than 100 precious manuscripts, early printed books (including the oldest print edition of the first-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus’s work), rings, seals, coins and ancient oil lamps, many bearing the image of a menorah.

On the first floor, “The Renaissance Speaks Hebrew” narrates a groundbreaking perspective that squares with much contemporary academic scholarship: that Jewish involvement in the Renaissance, largely omitted from standard histories, must be rediscovered and studied. “There is no Italian Renaissance without Judaism,” declares Giulio Busi, cocurator of the exhibition, from a monitor at the entrance to the installation, “and we would not be able to imagine Italian Judaism without the Renaissance.” Busi and his wife, Silvana Greco, both scholars of the Renaissance, assembled the show and edited its catalog. The full exhibition was on view from April 12 to September 15, 2019, and has now been abridged into a second permanent exhibition.

“Italians take great pride in the Renaissance,” says Michael Berenbaum, the original project director of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and an internationally recognized expert on Jewish museums. “It’s Italy’s greatest moment. If Jews were an integral part of it, then Italians should learn about it. Part of the message of any diaspora community has been that where Jews have been given freedom and accepted as participants in society, the society itself has flourished.”

For visitors seeking something lighter, a courtyard exhibit, organized as a labyrinth, instructs strollers on the do’s and don’ts of Jewish culinary laws, a kind of Garden of Finicky Kashrut. Elsewhere in the museum, a 24-minute video outlines the sweep of Italian-Jewish history. Other video monitors throughout the museum present statements from a selection of contemporary Ferrara Jews about their links to the community. One video features Andrea Pesaro, age 80, who until recently was president of the Ferrara Jewish community. Bassani based his famous novel on Pesaro’s family, the Finzi-Magrini. Since no real Finzi-Contini garden awaits literary pilgrims to Ferrara (Bassani invented the garden, just as he tweaked the name of the family), we watch as Pesaro takes his grandson through his own family’s garden and estate.

“PART OF THE MESSAGE OF ANY DIASPORA COMMUNITY HAS BEEN THAT WHERE JEWS HAVE BEEN GIVEN FREEDOM AND ACCEPTED AS PARTICIPANTS IN SOCIETY, THE SOCIETY ITSELF HAS FLOURISHED.”

“The Garden of the Finzi-Continis was, for our family, quite painful,” Pesaro says. “The professor in the film comes from my grandfather, Silvio Magrini. My mother becomes Micol. My uncle Umberto is Alberto. The only one whose name remained unchanged was the dog. When the book came out, there was a rather violent reaction, especially from my father.” The family objected to Bassani’s depiction of the Finzi-Contini as blasé about the threat from Fascism. Bassani, in turn, objected to De Sica’s alterations of his screenplay and withdrew all cooperation on the film.

The controversies about Bassani and the video of Pesaro capture in microcosm the convoluted era of Italian Jewry that serves as the museum’s biggest curatorial challenge: how to portray Italian Jewry during Fascism and the Shoah and get it right. One might start with the last part of the museum’s name—“E della Shoah” (“and the Shoah”). Read one way, it can sound like an aberration, an effort to treat the Shoah as a late add-on—as if someone had named a museum “The Museum of Modern Art—and Some Postmodern Pieces That Don’t Fit.” But is Fascist Ferrara an indisputable central chapter in the story of Italian Jews? Or was it, and Italian Fascism in general, just a tragic page, properly limited, contextualized and placed in its appropriate slot amid a 2,200-year history?

Arguments about the period escalated in 1961 with the publication of the most influential and debated work of scholarship on the Holocaust and Italian Jews, Renzo De Felice’s The Jews in Fascist Italy. Since it came out, every scholar of the subject has faced off with De Felice. Jewish himself and a longtime professor at Rome’s La Sapienza university, De Felice insisted that Italian Fascism and Nazism differed sharply, with Mussolini and Fascism lacking Hitler and National Socialism’s “biological” anti-Semitism. Almost all historians of Italian Fascism acknowledge that for the first 16 years of Mussolini’s regime (1922-1938), the Fascists largely avoided harassing Jews, and thousands of Italian Jews supported and joined the party. Mussolini himself famously referred to Nazism’s crude biological racism in 1934 as roba da biondi, “blond bullshit,” though his remarks about Jews from 1922 until his death in 1945 are rife with contradictions.

ONE REASON FERRARA GOT THE NOD FROM MEIS’S FOUNDERS IS THAT IT CONTINUES TO HAVE AN ACTIVE, IF TINY, JEWISH COMMUNITY, AS WELL AS A NON-JEWISH POPULATION THAT LARGELY APPRECIATES ITS PRESENCE.

De Felice’s view initially triggered enormous disagreement, with multiple scholars on Italy’s left labeling him an apologist for Fascism. His perspective, however, fit with a broadly held generalization accepted by many postwar Italians: that Italians behaved far better than Germans during the war, at least before the Germans occupied the northern half of Italy in 1943. It’s indisputably true that Italian Jews, compared to German or Polish Jews, suffered fewer deaths and forced departures to concentration camps. In his edited collection of essays, Jews in Italy under Fascist and Nazi Rule, 1922-1945, Yeshiva University historian Joshua Zimmerman noted that “about eight out of every ten Italian Jews survived the war.”

Nonetheless, the “upbeat story” of Italian Jewry under Fascism faced a serious assault from scholars beginning in the late 1980s. They began to establish, as American author Alexander Stille maintains, that the behavior of Italians, often previously compared to that of the Danish (under whom Jews fared the best during Nazi occupation), fell far short of the myth. The historian Liliana Picciotto, whose Libro della Memoria remains the most exacting account of the Italian deportations, calculated originally that 6,806 Italian Jews were deported after the Nazi occupation in 1943—6,007 to Auschwitz—and only 363 returned. In a later edition she raised the number of deportees to almost 9,000.

Every Jewish museum exists within the context of its particular community, whose sometimes changing sense of history, politics and ethos exerts influence on how that museum sees itself, with tension sometimes the result. Peter Schafer, director of the Jewish Museum Berlin, resigned in June under pressure from the Central Council of Jews in Germany and the Israeli government, who felt that the museum’s adversarial tilt against Israel had gone too far. The POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw faces turmoil with Poland’s conservative government. And in Hungary, the new House of Fates Holocaust museum in Budapest, which has yet to open, is mired in controversy over the museum’s attempt to downplay the country’s role in the Shoah.

Italy, too, has its own unique Jewish history to contend with. To fully understand or pass judgment on the Ferrara museum, one needs to grasp the anomalies of Holocaust culture in Italy and what Alexander Stille has described as Italy’s historical seesawing between “extremes of persecution and tolerance.” It’s that very history that the museum tries to make sense of in a third, newly opened exhibition (with a focus on Ferrara) that takes visitors from the Jewish ghettos to liberation in the 19th century as part of the Risorgimento, the successful political movement to unify Italy. A fourth exhibit will zero in on Italy and the Shoah—perhaps the museum’s most daunting task.

On the one hand, director Della Seta has to confront the ghettos and deportations, the Fascist devastation of Jewish civil rights, the silence of Pius XII during the Holocaust, and a Catholic Church hostile to Jews until recently. On the other hand, she must acknowledge the open-armed welcome Jews received for centuries from cities such as Ferrara, the prospering of Jewish prime ministers and generals after the Risorgimento, and the extraordinary acceptance of Jews as fellow Italians by their countrymen.

Della Seta has a personal link to the Holocaust. “I had five members of my family killed in the Shoah,” she states matter-of-factly, when asked. “They were deported from Rome on October 16, 1943. My grandfather and my uncle on one side, and my grandmother and two aunts on the other.” But she will not be curating on an emotional basis, she says. “I was born after the war, and I was the first generation in my family after the war. I processed that, and I don’t want my identity to be shaped by the Holocaust. I have chosen long ago a path of Jewish life. I am trying in my very little way to give a small contribution to Jewish life.”

That contribution will not include making MEIS a forum for contemporary arguments about Israeli policy or BDS. Sidestepping direct comment on the controversies in Berlin, Poland and Hungary, Della Seta declares, “We don’t discuss political issues. It’s too much. I don’t think this museum, by law, has a mission of speaking about Israel.” Then, with a twinkle in her eye, she adds, “Of course, we speak about Jerusalem when we speak about Titus and Flavius Josephus.”

Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, chief curator of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, says every museum must decide whether it wants to be “a modern museum,” where “history is a starting point for debate,” or a “traditional museum” that emphasizes “consensus” and a belief in “objective history.” She favors the former and sees the POLIN Museum and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum as models. In her view, MEIS’s success will be judged by the answer to a straightforward question about the story it tells: “Is it being presented as a kind of triumphalist account of the glories of the history of Italian Jews, with Ferrara as this wonderful place, or is it what we would call a critical history, a history that is dealing critically with all dimensions of the story?”

Berenbaum, who, like Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, has not yet visited the museum, lived in Italy in the 1970s. He expresses hope that MEIS will recognize that it can tilt toward the museum modernism he also favors so long as its exhibits are “based on serious, detailed scholarship and rooted in facticity.” He hopes the museum will be open to representing all points of view. “A museum can host controversy without being controversial,” he says.

One reason Ferrara got the nod from the founders of MEIS is that it continues to have an active, if tiny, Jewish community, as well as a non-Jewish population that largely appreciates its presence. Massimo Torrefranco, the Roman-born vice-president of the Jewish community—and Della Seta’s husband—offers a tour of the group’s historic home at Via Giuseppe Mazzini 95. Originally housing two synagogues (German and Italian), it’s the oldest Jewish communal building in Italy still in use. Damaged in the 2012 Emilia region earthquake, it is currently open only to members of the community.

In 1861, when most of the Italian peninsula’s individual states came together to form the Kingdom of Italy (a major accomplishment of the Risorgimento), Ferrara had a Jewish population of about 3,000 in a city of 33,000. Torrefranco, stylish in a white Panama hat over a kippah, explains that while the community numbers only 80 today, his outlook is upbeat. He thinks the museum will help attract young Jewish families to Ferrara. “It will be a magnet,” he says. He also notes that Ferrara benefits from its university, one of the oldest in Italy, which draws Jewish students from around the world.

Asked about the attitude of Ferrara’s non-Jewish residents to the new museum, Torrefanco smiles. “The average gentile in Ferrara is very familiar with Jewish culture,” he says. “They consider it part of their own heritage, even though there are very few Jews left.” Overt anti-Semitism in the city, he continues, is extremely rare. “For instance,” he points out, “one of the focuses for anti-Semitic acts and vandalism all over Europe is always the cemetery. And we haven’t had anything. The cemetery is particularly beautiful, huge and authentic. It is also quite exceptional in that it is owned by the Jewish community—it is not state- or city-owned land given to the community. It is ours.”

Generally, the attitude toward the museum is positive, he says, because people “see it as an opportunity to increase tourism in Ferrara and possibly to generate more work.” And, of course, there’s always the Bassani factor—the focus of unending local interest. This year The Garden of the Finzi-Continis was the subject of the city’s high school exam. Its renowned author lies buried here in the Jewish cemetery, far out in its most distant corner, under the towering cypresses.

Altri contenuti

4 marzo 2026: 110 anni dalla nascita di Giorgio Bassani

12 marzo, evento online

8 marzo, incontro su Giorgio Bassani

12 febbraio, evento online