A New Museum Explores 2,000 Years of Jewish Life in Italy

By Harry D. Wall

The epigraph etched in Latin on the ancient stone tablet was short and tender: “Claudia Aster, prisoner from Jerusalem.” Brought to Rome in chains after the quelling of the revolt in Jerusalem in 70 A.D., she was apparently the concubine of a Roman notable who wanted to give her a dignified burial and added an unusual element to the funerary stone. “I pray,” it said, “take care and follow the law that no one should remove the inscription.”

That tribute is one of many revelations at the new Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah in Ferrara, and is at the heart of the museum’s first major exhibition, “Jews, an Italian Story. The First Thousand Years,” which examines the long and complex relationship between Rome and Jerusalem, Christianity and Judaism.

Jews have lived on the Italian peninsula for more than 2,000 years, one of the oldest communities in the Western Diaspora. Even before the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, then the centerpiece of Judaism, and the ensuing transport and enslavement of Jewish prisoners to Rome, there had been Jews living in the city and southern provinces, where they had arrived as traders and refugees.

The history of Jewish life in Italy might seem like one long saga of suffering and trauma: slavery by the Romans; the Inquisition and persecution by the Church; forced segregation to cramped neighborhoods in the Middle Ages. The first of many ghettos was established in Venice in 1516. The 20th century witnessed the rise of fascism, anti-Semitic racial laws and the Holocaust, when nearly 7,700 Jews out of a total population of 44,500 were killed.

However, there is another part to the Italian Jewish story, one of acceptance, integration and even appreciation throughout the long arc of civilization on the peninsula. “The historic dialogue with the culture of Italy has enriched Italian Judaism and has also brought to the Italian culture much of Jewish values and contribution,” said Simonetta Della Seta, who was appointed the museum’s director in 2016.

As the museum moves chronologically through the eras of Italian history, additions are being made to the permanent exhibit. The second major exhibit opened in April, on Jews and the Renaissance. The Holocaust will be addressed by the museum with a permanent exhibition that will open in September.

Ferrara, in northeastern Italy between Bologna and Venice, and once a medieval center of Jewish life, might seem like an improbable choice for the museum, known in Italy as MEIS, for Museo Nazionale dell’Ebraismo Italiano e della Shoah. A once important Renaissance city dominated by a large castle, the hub of the powerful Este family, and ringed by medieval walls and ramparts, Ferrara is off the beaten path as far as Jewish life and popular tourism in Italy is concerned. MEIS may change that.

The museum is partly built on the converted remains of a former prison on Piangipane Street, a two-story brick compound near the former Jewish ghetto. Used to detain anti-fascist partisans and Jews during World War II, it was closed in 1992.

So why choose a former prison to house the new museum? “The challenge is to take a place where people were closed in, where it was dark; transform it into an open space, open to ideas, open to culture, open to dialogue, and this is our mission,” Ms. Della Seta said.

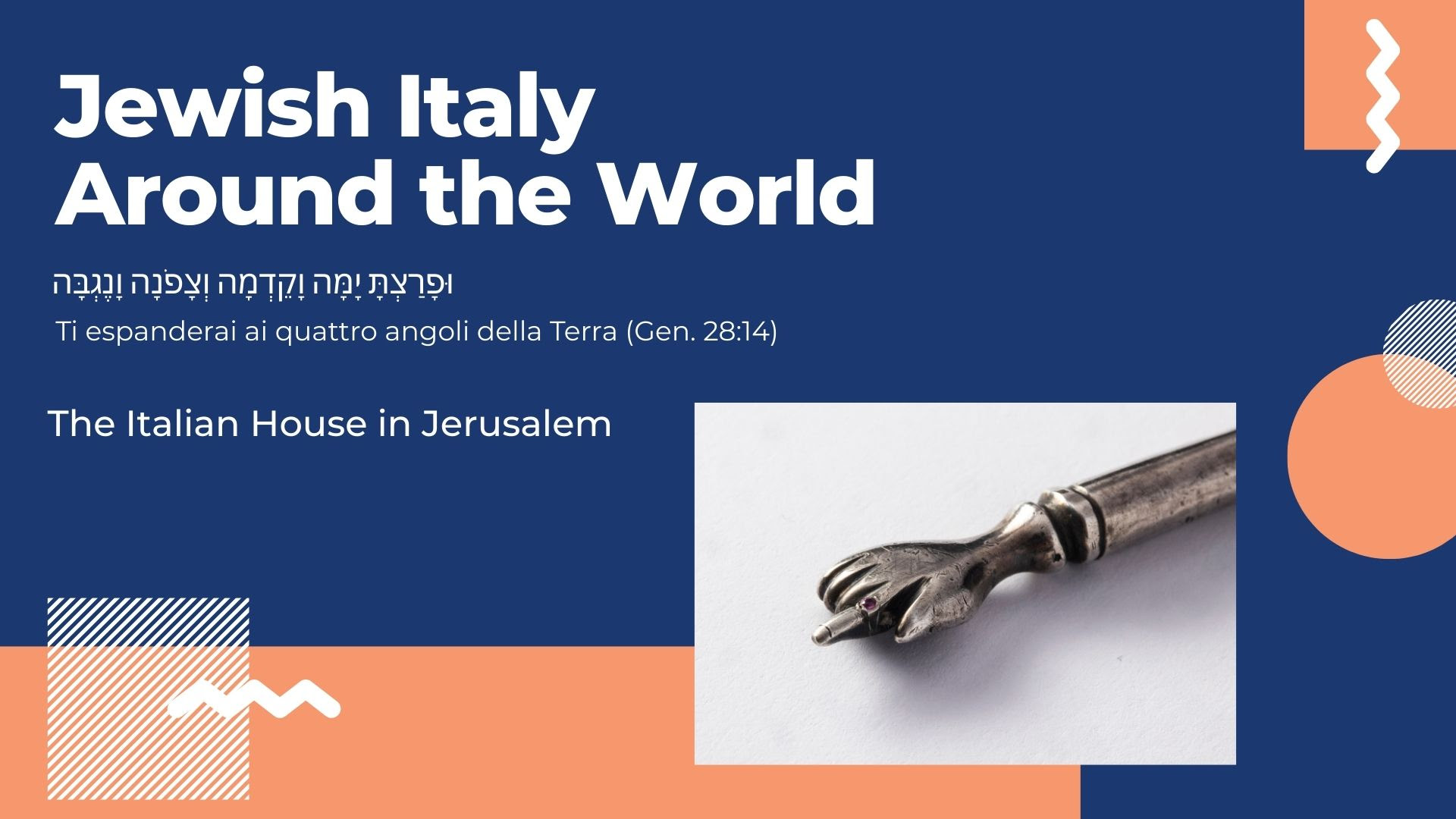

The museum’s collection of more than 200 artifacts and multimedia installations supports that alternative narrative, of coexistence and contribution. A fifth-century mosaic of two matronae, one with the Old Testament, the second with the New, shows a single community of faith, a chapter in an otherwise fraught relationship with Christianity. There are precious documents and instruments depicting Jewish contributions to medicine, science and astronomy.

Also on display are fragments of ancient manuscripts and texts, highlighting the importance of literacy in Italian Jewish history.“Jews for centuries were the writers, the scribes. Then they became the printers of the Italians,” Ms. Della Seta said. She noted that among the first publishers in Italy during the medieval era were the Jewish printing houses in Venice and Soncino.

Ferrara represents what was, for a time, a golden era of Italian Jewry. It was the policy of the Duke of Este in the 16th century to welcome Sephardic exiles from Spain and other Jews to the city, a period when the Church was ascendant and Jews were being confined to ghettos in Rome and Venice.

“The Duke understood that the Jews, being mainly merchants and traders, could contribute to the Estes’ ambition to grow the textile industry of Ferrara,” said Andrea Pesaro, 80, a retired engineer who now lives in Milan but returns often to his hometown, where he is head of the small (80 person) Jewish community.

At its peak in the Middle Ages, about 2,000 Jews lived in Ferrara, Mr. Pesaro said. They included notable scholars, doctors and printers. But after the reign of the House of Este ended, the church became ascendant, anti-Semitic persecution intensified and Jews were confined to living in a ghetto from around 1627 until the emancipation in 1859.

Jewish life in Ferrara

“Jews have been living in Ferrara for over 1,000 years,” Mr. Pesaro said as we stood in front of the synagogue building on Via Mazzini, 95, on its original site since 1603 and renovated many times since then. It is now being repaired after sustaining serious damage from the earthquake of 2012. The building is simple, red-bricked and almost undistinguishable from others on the street except for the two plaques next to the arched entrance, commemorating the victims of the Holocaust from Ferrara. There are two synagogues inside. The larger, the Ashkenazi synagogue, with its barrel-vaulted ceiling, multiple chandeliers and bright Jewish drawings on the walls, contrasts with the simple dark wooden pews and Torah ark.

A walk through the former ghetto with Mr. Pesaro provides a moving glimpse into a distant time. Via Mazzini, once the main ghetto street, is now dotted with cafes and shops. It bustles with bicyclists riding to the nearby main square of the historic district, dominated by the cathedral and moat-ringed castle. Jewish life is invisible to all but the most discerning pedestrians.

Two narrow cobblestone streets, adjacent to Via Mazzini, form the more recognizable heart of the ghetto. We walked on one, Via Vignatagliata, as Mr. Pesaro pointed out buildings that once housed the matzo bakery (No. 49) and the Jewish school (No. 79), whose numbers swelled after Jews were barred from attending public schools by the racial laws of 1938. On the left is a small square, Piazzetta Isacco Lampronti, named after a renowned rabbi, scholar and physician of the 18th century. At night, however, when the winding, narrow streets seem so melancholy under dim lights, it is easy to imagine that dark time for Ferrara’s Jews.

The Jewish cemetery, outside the ghetto, is startling, if only for its sprawl and large grassy areas, free of headstones. When I asked Mr. Pesaro where all the gravestones had gone, he explained that the marble and stone were taken during the Inquisition in the 18th century, when some were used to build the two pillars framing the municipal hall across from the cathedral.

The cemetery draws many visitors, Italian and foreign, mainly to pay tribute to Giorgio Bassani, the distinguished Jewish writer from Ferrara, best known for his novel, “The Garden of the Finzi Continis.” A tilting bronze headstone, with a jagged facade that pierces through a stone base, marks his grave, isolated in the cemetery. The book, later made into a movie by the same name, is about a wealthy Jewish family contending with the racial laws of 1938 and about to be engulfed by the Holocaust. It is a source of contention for Mr. Pesaro and others in the community, who feel Bassani offended his family, on whom the book seems to be based, by depicting them and the Jews of Ferrara as out of touch with fascism and their impending doom.

An evolving museum

The museum is a public, state-funded institution, proclaimed by the Parliament of Italy in 2003. Originally conceived as a museum of the Holocaust, its mission was changed later to encompass the history and heritage of Italian Jewry. It was inaugurated on Dec. 13, 2017, in two of the former prison buildings that were renovated and designed by an international team based in Milan. Four new buildings, designed to look like five, inspired by the books of the Torah, are to be added so that by its completion in 2021, the museum will contain nearly 100,000 square feet of space, at an estimated cost of $50 million.

At the entrance, visitors are encouraged to watch a 24-minute video (in English and Italian) that conveys the sweep of Italian Jewish history through individual stories — a Jewish slave, deported from Jerusalem to Rome in the first century, a scholar from the Middle Ages who enjoys a privileged status, and a young girl in 1938, forced to leave school as a result of the racial laws. Following that compressed virtual history, a short walk leads to the second building, crossing an educational garden where visitors can learn about Jewish dietary laws.

The “First Thousand Years” exhibition is largely focused on Rome and the southern regions — Sicily, Puglia, Campania, Calabria — as that is where Jews mainly settled during the first millennium. After passing a replica of the Arch of Titus, commemorating Rome’s victory over Jerusalem, and depicting soldiers carrying the seven-branched menorah, visitors are offered a well-lit and spacious display of original and replicated artifacts: ancient engravings, amulets, rings, seals and oil lamps with Jewish symbols, medieval manuscripts, some now on permanent loan from other national Italian museums.

There are complete chambers, simulating the Jewish catacombs in Rome, their walls adorned with frescoes of menorahs, other religious symbols and Hebrew lettering. “The Jewish catacombs in Rome were a treasure trove for our knowledge of Jews in the Imperial Age, about 40,000 people,” said Ms. Della Seta.

The display is thematic as well as chronological. The dispersal of Jews throughout the Italian peninsula, the relationship between Jews and Christians, the contribution of Jewish scholarship and science to the broader civilization. Video monitors are strategically placed featuring experts — historians, archaeologists and rabbis — explaining their choice of artifacts or historical events.

What comes across throughout the two-floor exhibition is the breadth and tenacity of Jewish life over the millenniums. The Italian peninsula witnessed serial conquerors — Romans, Goths, Byzantines Longobards and Muslims — who are all gone. Yet the one continuous presence has been the Jews, clinging to their identity and civilization in the face of severe challenges to their survival. There are about 30,000 Jews living in Italy today, the majority in Rome and Milan, according to the Union of Italian Jewish Communities, an umbrella organization.

The mission of the museum, said Dario Disegni, chairman of MEIS, is to foster dialogue, understanding and coexistence. “The MEIS tells the story of a minority, which was integrated in the Italian society and, at the same time, was able to maintain its identity, both cultural and religious, without being assimilated. It is really a model, a point of reference for the Italian and, more generally, Western societies of today.”

It is a message, at a time when Italy and other European countries are being tested by a new wave of immigration and rising intolerance, that might give MEIS a broader resonance and purpose than that usually associated with a history museum.

Altri contenuti

12 marzo, evento online

8 marzo, incontro su Giorgio Bassani

12 febbraio, evento online

Giorno della Memoria 2026, il calendario degli eventi