DIASPORA’S OLDEST COMMUNITY GETS A CONTEMPORARY SHOWCASE

By Barbara Sofer

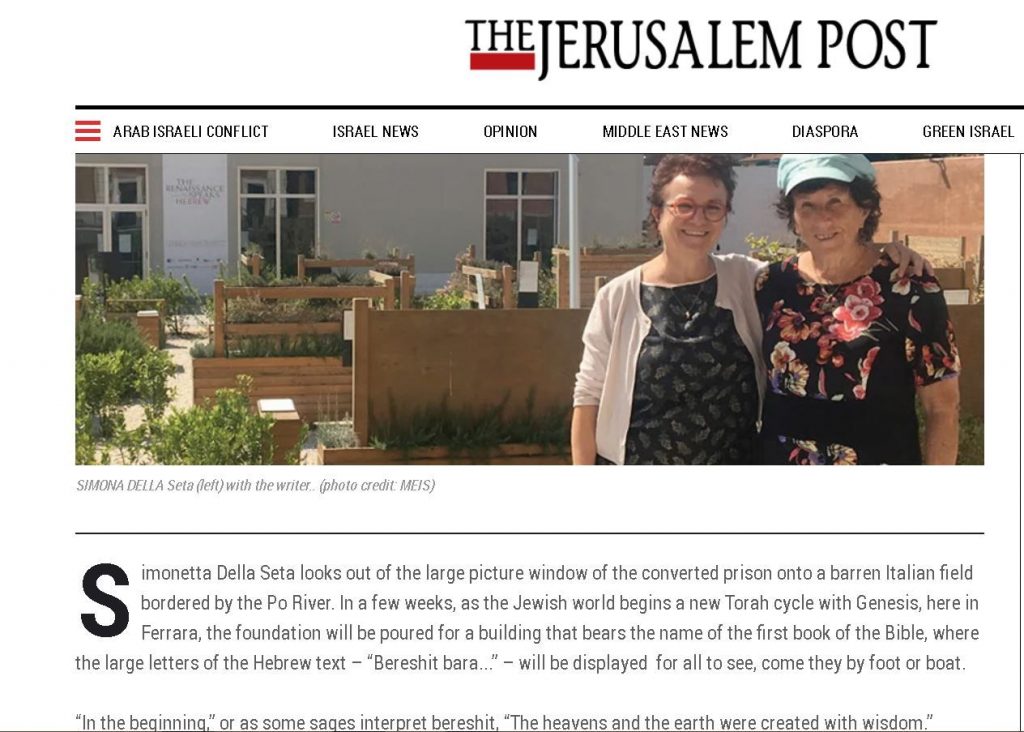

Simonetta Della Seta looks out of the large picture window of the converted prison onto a barren Italian field bordered by the Po River. In a few weeks, as the Jewish world begins a new Torah cycle with Genesis, here in Ferrara, the foundation will be poured for a building that bears the name of the first book of the Bible, where the large letters of the Hebrew text – “Bereshit bara…” – will be displayed for all to see, come they by foot or boat.

“In the beginning,” or as some sages interpret bereshit, “The heavens and the earth were created with wisdom.”

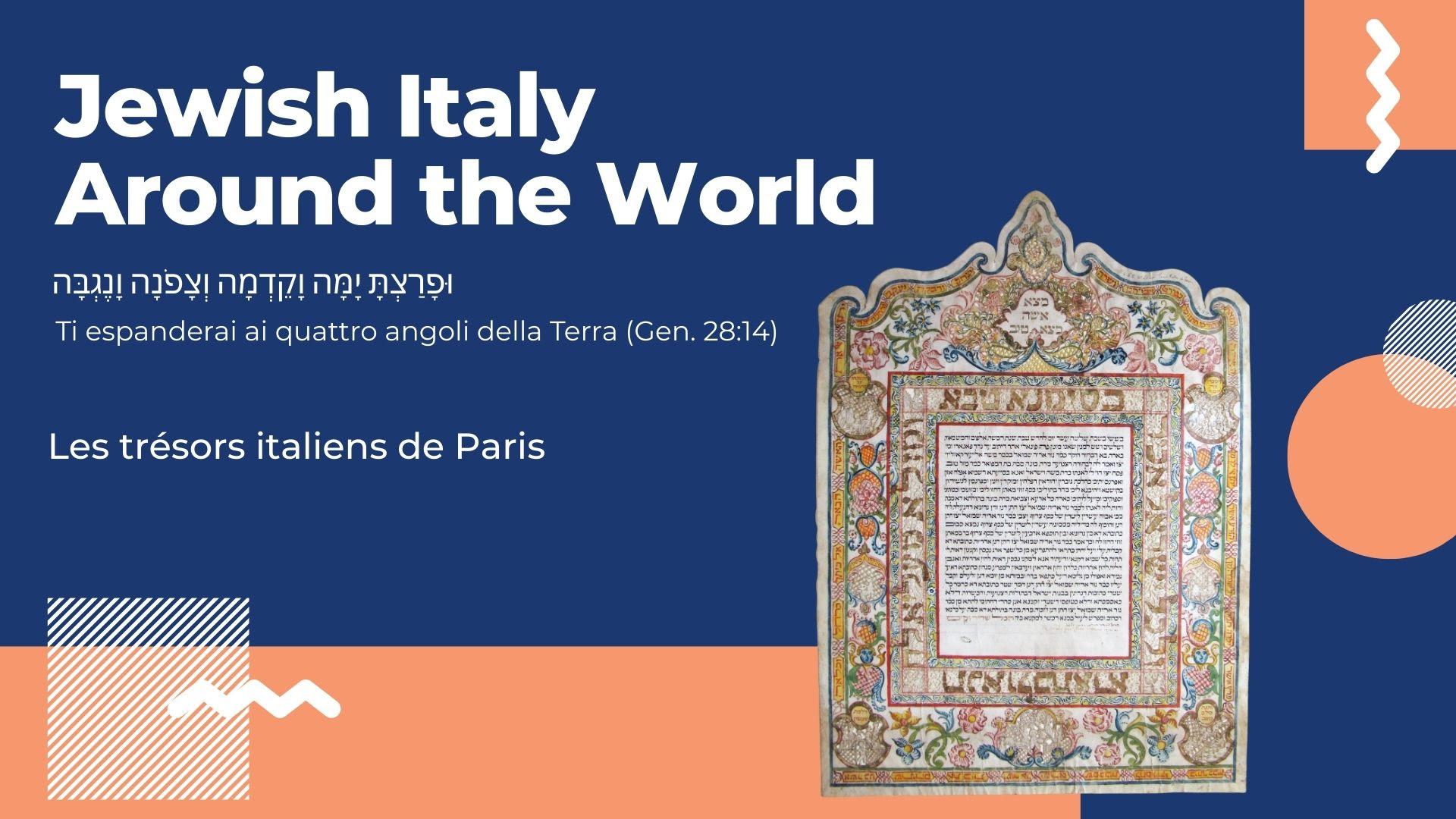

Wisdom/creative thinking is abundant in this museum of the Diaspora’s oldest continuous community. It’s called MEIS, an acronym in Italian for National Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah, and it is becoming the most important museum in Europe at a time when European Jewry faces an uncertain future.

Della Seta is the director.

On a recent seaside vacation in southern Italy, my husband and I drive our rented Fiat four hours north on the autostrada so we can see the museum and meet with Della Seta, whom I’ve long admired. She and her husband, musicologist Massimo Acanfora Torrefranca, have moved from Rome to Ferrara for this project. Torrefranca is also a leader in the Jewish community.

Five buildings, one for each book of the Torah, will join the prison buildings where Jews were held in the Holocaust.

In 2003, the Italian government committed to creating a national Holocaust museum, but later accepted the Jewish community’s amended plan to include the context of their history and achievements, not only the catastrophe of 8,000 Italian Jews murdered in the Holocaust. Della Seta was chosen unanimously to head it.

The government has allotted €46 million for construction on the 1-hectare (2.48-acre) site plus a modest €1m. a year for upkeep and programming. Della Seta will have to fund-raise for the rest, which she envisions as a center for education, inspiration and even destination weddings.

Ferrara, 113 kilometers south of Venice, was best known from the Academy Award-winning film The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, based on Giorgio Bassani’s novel, but MEIS is already attracting busloads of tourists to the sedate and charming walled city.

Jews were welcomed here by the ruling Este dukes after the expulsion from Spain and Portugal. The 1492 Sephardi synagogue was in use until the Fascists shuttered it in 1943. The beautiful Ashkenazi synagogue, with stucco depictions of allegorical scenes from Leviticus, will be full on the upcoming High Holy Days, in a building paid for by a Roman Jewish banker in 1485.

Although Della Seta is adamant that she makes no solo decisions – she reports to a board of directors plus government supervisors, and has engaged designers, rabbis, archaeologists from Italy and abroad through 37 public tenders over three years – her enlightened touch is everywhere. She comes to MEIS from a career as an illustrious journalist, author, historian and diplomat. Born in Rome to Holocaust-survivor parents, she has traditional Jewish roots and is an awardee of the Order of the Star of Italy. She switches easily from Italian to fluent Hebrew and English.

Because the museum is new, Della Seta isn’t encumbered by an existing collection of glass-cased artifacts. This enables her to engage visitors, particularly millennials and schoolchildren, with stories. She is determined to reveal the depth and complexity of the relationship between the Jewish minority and non-Jewish majority, emphasizing the unique Jewish story while suggesting a universal subtext of needed tolerance.

THE JEWISH story begins, of course, in ancient Israel, but by the time of the Maccabees, Jews are already living in Rome. Two centuries later, in 70 CE, Roman General Titus captures Jerusalem and destroys the city and the Second Temple, returning to Rome in triumph with the Temple treasures and Jewish slaves. Roman Jews redeem many, but according to Della Seta, the pillaged Temple vessels were on display for two years, and then used to pay for the construction of the Colosseum, built by Jewish slave laborers. An unearthed Colosseum inscription, displayed at the museum, confirms the funding source.

A life-size statue of Titus that was buried in the volcanic destruction of Pompeii in 79 CE signals the entrance to a room where virtual fires burn on all sides at the fall of the Second Temple, which occurred nine years earlier. The destruction of Pompeii was viewed by both Jews and Romans as punishment for the destruction of the Temple. “You see, there is another story behind the story,” says Della Seta.

Nuance doesn’t disguise the dark side. The 2019 exhibit “The Renaissance Speaks Hebrew” shows the overlap between Jewish and Christian culture, highlighting the accurate and respectful use of Hebrew in Renaissance art. An excruciating video describes how Jewish banker Daniele da Norsa is forced to pay for commissioning a church painting by Andrea Mantegna, who subsequently paints abased images of the da Norsa family into another “Madonna and Child.” Also exhibited is the horrific wooden frieze of Jews supposedly sacrificing a child named Simon for matzah-making. The frieze greeted worshipers in the Trent parish church from the 16th century until the 20th century, when Simon’s sainthood was revoked.

The stories are told through a mix of originals and facsimiles. Many of the originals were languishing in other museums and archives where few appreciated their Jewish interest. For example, a two millennia-old tombstone of Hebrew slave girl Aster was in the national museum in Naples. What may be the oldest-ever, exquisite silver Torah crowns (rimonim) from 15th century Sicily wound up in the Cathedral museum in Palma de Mallorca. From the state archive in Florence emerges a contract, handwritten by Piero di Antonio da Vinci – Leonardo’s dad – for the opening of a dance school staffed jointly by Jewish and non-Jewish dance teachers.

Equally interesting are the reproductions of the hard-to-access Roman Jewish catacombs, like those beneath the Villa Torlonia, where Mussolini lived for 18 years and reportedly created an underground bunker.

Linking the two buildings of the prison are trees planted in honor of Israel’s 70th anniversary, and the Garden of Questions, with plants connected to Jewish dietary laws. You can take the meat recipe trail or the dairy one.

The completed museum will feature Ferrara’s first two kosher restaurants – also meat and dairy – as well as a hall for celebrations. MEIS is already serving as a venue for cultural events, including talks by Israeli writers. On the day before our visit, 40 Italian teachers came for a seminar on teaching the Holocaust.

The outlines of the prisoners’ cells have been preserved by the architects in the administrative floor of the three-story main building.

Says Della Seta, “My modest office is made from four cells – that means 24 prisoners were imprisoned there. Now it’s only me. I think of them often.”

Altri contenuti

12 febbraio, evento online

Giorno della Memoria 2026, il calendario degli eventi

Giorno della Memoria 2026, il programma per le scuole

Viaggio alla scoperta del Salento ebraico