An Italian Institution's Antidote to anti-Semitism? Telling the 2,000-year History of the Country's Jews

by David B. Green

A new museum in Ferrara, Italy shows that the remarkable story of Italian Jewry is inextricably intertwined with the country’s history.

Although it once hung in a church in Mantua, these days, if you want to see “Madonna of Victory,” the 1496 painting by Renaissance artist Andrea Mantegna, you’ll have to travel to Paris, to the Louvre. The painting, festive while being devotional, celebrates a dubious military victory by the Mantovan Marquis Francesco II Gonzaga over the French forces at Fornovo in 1495. The work was commissioned for the Santa Maria della Vittoria church, in Mantua, where it was on display for three centuries, until Napoleon invaded Italy. His victorious army took the altarpiece as booty and shipped it back to Paris, where it remains to this day, giving the French the last laugh, some might say.

But there’s an older, more fundamental backstory to the “Madonna of Victory,” about a Jewish banker named Daniele Norsa, who was coerced not only into paying Mantegna’s sizeable fee of 110 ducats for the painting, but also into forfeiting his home so that a church could be built in its place. To learn that tale, one would do better to visit the new National Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah (known for short by its Italian acronym, MEIS) in Ferrara. There you can read the sorry saga of Norsa, who, at the time he purchased the house a few years earlier, had requested permission from the local bishop to remove the Christian images, which included the Virgin Mary herself, painted on its external walls.

In a fascinating essay appearing in a MEIS catalog, art historian Salvatore Settis explains that Norsa not only wanted to eliminate the symbols of a religion he did not identify with, but also was fearful that if some harm were to come to them, he would be the one accused of sacrilege. Although Norsa was granted the permission he sought, and proceeded to take down the images in question, he didn’t clear his sensitive request with all the relevant players, and soon found himself under attack. Pressured by public and clerical anger at Norsa’s ostensible blasphemy, the marquis ordered him, on pain of death, to pay for the celebratory painting and to relinquish his house and property so that a proper home could be built for it.

The tale of Daniele Norsa, the involuntary and unrecognized donor of this Renaissance masterpiece, is one of many surprising stories to be gleaned at the MEIS, which itself constitutes something of a surprise. The museum opened only two years ago in Ferrara (some 90 kilometers southeast of Mantua), and both its premises and its permanent exhibitions are still far from complete. In fact, it has no collection of its own, and most of the objects it shows are on loan from other museums along the length of the Italian peninsula, which collectively go a long way to telling the 2,000-year narrative history of the country’s Jews. Indeed, like other newly established, state-of-the-art museums, MEIS sees its mission more as telling a story than of accumulating and showing objects.

The very choice of Ferrara – a city of some 130,000 residents situated in the country’s northeast, midway between Venice and Bologna – as the site for a new national museum, may seem counterintuitive. Rome, after all, is the capital, draws millions of tourists a year and has had a Jewish presence since prior to the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, in 70 C.E. But there are good reasons for Ferrara being the choice, and they too are part of the story told at MEIS, which last month opened a temporary exhibition on “Jewish Ferrara.”

If you have any association to the town of Ferrara, it may be by way of “The Garden of the Finzi-Continis,” whether the 1962 novel by the Italian-Jewish writer Giorgio Bassani or its 1970 film adaptation by director Vittorio de Sica. Bassani (1916-2000) was certainly the city’s best-known literary figure. Although he moved from Ferrara to Rome after World War II, he spent the rest of his life writing about the former, drawing in large part upon the decades he had spent there while growing up. (In 2018, Bassani’s collected stories and novels about his birthplace were published in a single volume in English, titled “The Novel of Ferrara.”) Many of Bassani’s sharply drawn characters are based on recognizable denizens of the town, particularly its Jewish community. Which helps explain why to this day, so many Ferraran Jews have mixed feelings about him.

Giorgio Bassani, however, receives almost no mention in the new museum exhibition (which is open through March 1, 2020), leaving one with the impression that he will have to wait to receive an entire show of his own.

Simonetta Della Seta, founding director of MEIS, explained how the germ for the idea was planted in the unanimous decision of the Italian parliament in 2003 to establish a national shrine commemorating the Holocaust. When the authorities began discussing that idea with leaders of the Jewish community, she says, what they heard was that, “‘We don’t think Italy can have a Holocaust museum without telling the long and rich history of Italian Jewry. It was clear to everyone that the Italian case was unique, because it is the only place in the Diaspora where Jews have lived continuously for 2,200 years, with no interruption.”

Although Italy’s Jewish population never exceeded 50,000, Della Seta stresses that “the role of Italian Judaism goes far beyond the numbers, because via Italy, in a very natural way, Jews went from the Land of Israel into Europe.” (I should note that Della Seta, a journalist and historian who ran the Italian Cultural Institute in Tel Aviv for several years, is a close friend.)

At about the same time as the government was discussing what it might do, the Rome municipality began planning its own memorial to the Holocaust (to date, unfinished), so even before the focus of the new national museum was resolved, it was decided not to situate it in the capital. Still, one may ask, why Ferrara?

A windowful of Ferrante

Above all, Ferrara has a long and rich Jewish history. There is written evidence of Jews living in the town as early as 1227, with a notarized document from that year referring to one Sabatinus Judeus. But it was during the rule of the princely Este family, which lasted from 1240 to 1597, that Jews – moneylenders, but also physicians and religious scholars – were actively invited to settle in Ferrara. As British historian Simon Schama writes in “Belonging, 1492-1900,” the second volume of his “Story of the Jews”: “The Este [dynasty] hoped that the Jews would turn their city on the Po into the Antwerp of north Italy, the transit point in trade with the Adriatic coast, and transform a backwater into a modern commercial centre to rival Florence.”

In 1493, Duke Ercole Este I allowed 21 Jewish families who had been expelled from Spain the preceding year to settle in his city. “They were given rights of unlimited residence and free worship, a liberal hospitality which existed nowhere else in Christian Europe,” writes Schama. Eventually, Ferrara had representatives of Ashkenazi, Sephardi and Italian Judaism.

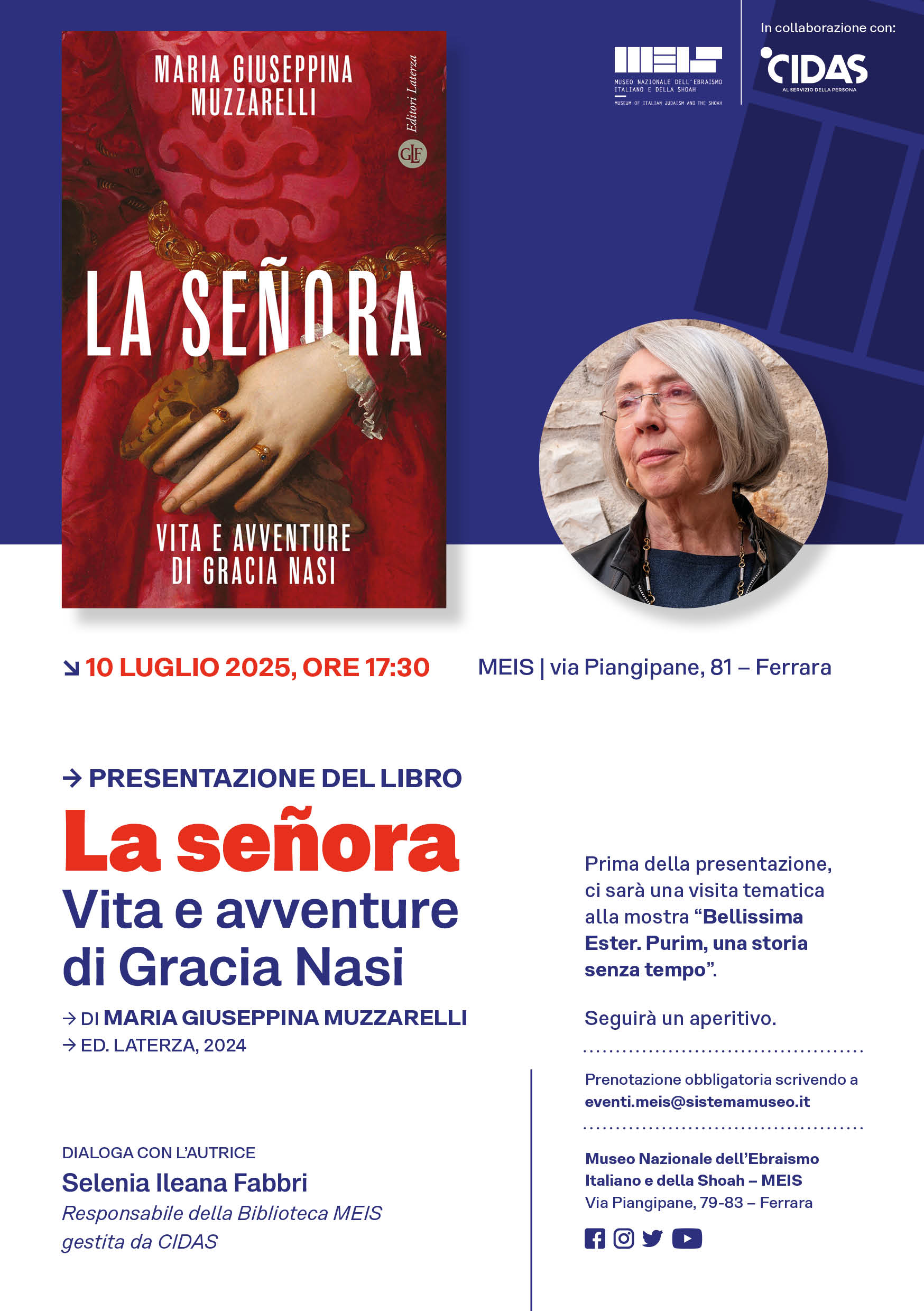

Some of the most prominent of the Iberian exiles either settled in Ferrara, or used it as a way station before moving further east to the lands of the Ottoman empire. They included the financier and scholar Samuel Abravanel, who moved there with his wife Benvenida from Naples in 1541, and the legendary Dona Gracia Hanasi, widow of the financier Diogo Mendes, who succeeded in smuggling out her late husband’s fortune from under the nose of the Portuguese king, and set up a secret network to help Jews escape from Inquisition-era Portugal, before she herself continued on to Constantinople.

The Jews of Ferrara were permitted to establish their own cemetery, outside the city walls, and long after their brethren in the rest of the Italian peninsula were confined to ghettos, they were free to reside wherever they desired. They were restricted to a ghetto only in 1627, after the last duke of Este, Alfonso, died without a male heir, and the city came under papal rule.

The Ferrara ghetto was in the city center, in a neighborhood where the Jews had already settled themselves, flanking both sides of what is today Via Mazzini, a bustling commercial street. At the northern end of Mazzini, next to the bookstore that today showcases copies of the new Elena Ferrante novel in one of its windows, one can see marks left in the wall by the hinges of one of the ghetto’s gates, which were dismantled with emancipation, in 1870.

If you head back toward the plaza between the cathedral (now closed for renovations) and city hall, one sees the statue of the Duke Borso d’Este, which stands atop a column composed of remnants of gravestones taken from the Jewish cemetery destroyed in 1716. A hundred meters from there, just before one reaches the majestic, moat-surrounded Este castle, one hits Savonarola Square, presided over by the ominous and forbidding figure of the 15th-century hooded friar. The harsh reformer may have been considered dangerous by the Church, which had him hanged and burned in 1498, but in his birthplace, he is something of a hero, if the 1875 statue by Stefano Galleti is any indication. Particularly in the dark of the evening, Savonarola is a chilling sight, but if you step into the Hosteria Savonarola behind the statue, you can warm up with a glass of wine and a dish of cappellacci di zucca, a characteristic Ferrara pasta dish, filled with pumpkin.

MEIS is a few minutes’ walk from the old ghetto, on Via Pangiapane. Today, it comprises two structures, both of them remnants of a state prison that opened in 1912 and was closed 80 years later. In 2006, the government decided to turn the site over to the foundation entrusted with establishing the museum.

Della Seta explained that the availability of the abandoned prison was the decisive factor in the decision to set the museum in Ferrara. “It was empty, it was part of a huge compound of 10,000 meters, and it was a governmental building.” Lending extra resonance to the location was the fact that the prison was used as a detention center for the Jews of Ferrara in 1943 before their deportation to Auschwitz. In total, 150 of the city’s Jews were arrested and sent there (out of a pre-war Jewish population of over 700), only five of whom survived.

Only two buildings from the original compound were preserved – a three-story men’s barracks and a two-floor entrance pavilion, both of them brick structures that have been handsomely restored. The plan for the museum, however, calls for the construction of five additional structures, to be shaped like books, and symbolizing the Five Books of Moses. Each of the narrow buildings will be faced with a semi-translucent glass curtain, on which will be etched verses from their respective books – in Hebrew, each letter 33 cms (13 inches) high, to the full view of the Italian public.

Ground broke this fall on the building symbolizing Genesis, and Della Seta forecasts that construction of the entire museum won’t be completed before 2025 – “but that’s just a guess,” she says, adding that the physical aspect of the museum is being overseen by the Culture Ministry. Fortunately, the Italian government has pledged to finance the entire physical plant, and is also supplying the museum with a million euros annually toward operating costs. To supplement that and the income from ticket sales, the museum has set up fundraising organizations both at home and abroad.

Bodyguards for Segre

Of course, the path from the pledging of funds to their eventual release can be lengthy and marred by political considerations, and Della Setta explained to me that the previous government (which was dominated by the populist deputy prime minister Matteo Salvini), withheld a payment of 25 million euros, claiming that the museum was behind schedule. On November 11, however, the new, centrist government announced dramatically that it was transferring the money immediately. It was probably no coincidence that the move came during the same week it was reported that Liliana Segre, an 89-year-old survivor of Auschwitz and Italian senator for life, had been assigned bodyguards after she had been flooded with anti-Semitic messages and threats.

The threats became especially intense following Segre’s introduction in the Senate of a bill to establish a government commission to fight online racism and hatred. That bill passed earlier this fall, but the ambivalent response of the Italian government to the growing xenophobia and anti-Semitism has drawn criticism both at home and internationally.

Ferrara’s new mayor, Alan Fabbri, belongs to the Lega (formerly the Lega Nord, or Northern League), the anti-immigrant party led by Salvini, who epitomizes the worst of Italian populism. Fabbri, though, has embraced his city’s Jewish museum. With a beard and ponytail that suggest college lecturer more than urban official, Fabbri was in attendance at the opening of the exhibition about Ferrara’s Jews last month, and noted in his remarks that his administration sees the museum as central to the goal of having Ferrara become part of a “Jewish itinerary” for tourists in the Emilia-Romagna region. He also promised that the Jewish community center, on Mazzini Street – which until it was damaged by an earthquake in 2012, housed the community’s three functioning synagogues – would be fully restored. It was also Fabbri who a few days earlier, had offered Liliana Segre honorary citizenship in Ferrara.

I asked Simonetta Della Seta about her museum’s relations with city hall. She is understandably reluctant to voice any personal political opinions (“I have to lead this project forward, whoever is in the government, and whoever is at the municipality,” she explained), but noted that “I only can say that they have been very nice with us, and we have good relations.”

The planners of MEIS have divided its content into four periods: the first 1,000 years of Italian Jewish history, the Renaissance, the period from “the ghettoes until emancipation,” and finally the 20th century, up to and including the Shoah. So far, the permanent displays cover the first two periods, and according to Della Seta, the latter two exhibitions will be set up by mid-2020, even if their final location within the museum’s shell will change as construction progresses.

During a mid-November visit of several days to Ferrara, I was never more aware of living within the flow of Jewish history, and of the inextricable intertwining of that history with Italian history in general.

‘Titus is like Hitler’

Near the entrance to the permanent exhibition, one encounters a beautifully preserved marble statue of Titus, the Roman general, later emperor, who conquered Jerusalem in 70 C.E. and destroyed the Temple. Simonetta Della Seta explained that it was not an easy decision to display an image of Titus, “who, in Judaism, is like Hitler.” But, when she laid eyes on the sculpture, she knew that it belonged in the museum.

“It was found,” she explains, “in the ashes of Pompeii, which was destroyed [by a volcano] in 79 C.E. Many among the Jews and among the Romans thought this was the punishment for Titus for destroying the Temple.” If the statue looks new, it’s because it was covered by lava only two months after being erected.

One also learns that the funds for the construction of the Roman Colosseum, which began in 71 C.E., came from the looted treasury of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. The museum’s catalog “Jews, an Italian Story: the First Thousand Years,” also tells us that, “of the nearly 100,000 prisoners from Jerusalem, those who reached Rome as slaves were set to work on these gigantic monuments” – referring not only to the Colosseum, but also to the Arch of Titus, as well as to the Temple of Peace (Temporum Pacis), which is where the ritual objects of the Jerusalem sanctuary were displayed, until the destruction of the Roman shrine by fire in 191 C.E.

While discussing plans to work with Italy’s schools, Della Seta mentioned how just a few weeks earlier, on October 28, MEIS had signed an agreement with the Colosseum, with which it will cooperate on devising educational programs intended to teach students about the Jewish place in Roman history. The signing ceremony, conducted in the ancient Roman senate building “was an amazing event,” she says.

This leads Della Setta to launch into a declaration about the multiple missions of MEIS, with “relevant” being the word employed more than any other.

“When you are telling such a long story, on the dialogue between the majority and a minority, and also of course, not always positive, it is relevant for the present.” Together with visitors to the museum, Della Setta says she has learned what a fitting setting it is for conversations about coexistence in general.

“Italy is a Catholic country, and the coexistence between Italian Jews and the surrounding society is probably the only experience Italy had [historically] with another culture. And so it’s relevant to have Italy showing European countries that there is such an experience here, and especially today, when we have so many immigrants, and so many problems connected with recognizing that other cultures exist, and that it’s not only Catholicism,” she observes.

The museum’s location in a former prison is also used to advantage. “This is a place with bad memories, a place where Jews were imprisoned before being taken to Auschwitz,” says Della Seta, adding that she is proud that she and her colleagues have turned it into “a cultural laboratory dedicated to dialogue. We have events and speak about the Sinti and Roma, and we speak about Armenians. It became a place where it is easier to speak about these subjects, because it is the core of what we do.”

For Della Seta, these things are also a much more effective educational response to the Holocaust than a memorial dedicated directly to the subject. “To spread knowledge about who the Jews are, about how they have been here for so long, and what they have contributed to the country. This, to my eyes, is our response to anti-Semitism, our antidote. It’s is the best thing we can do. Instead of speaking about ‘Shoah, Shoah, Shoah.’

“When the media come to interview me on January 27 [International Holocaust Day], I will take them in front of the Arch of Titus [model], and I will speak about how Jews have been here all the time, and they were integrated into Roman society, into society of the Middle Ages, into Renaissance and Risorgimento society – then they get a different perspective on the discussion of the Shoah and on anti-Semitism.”

Altri contenuti

10 luglio, evento in presenza

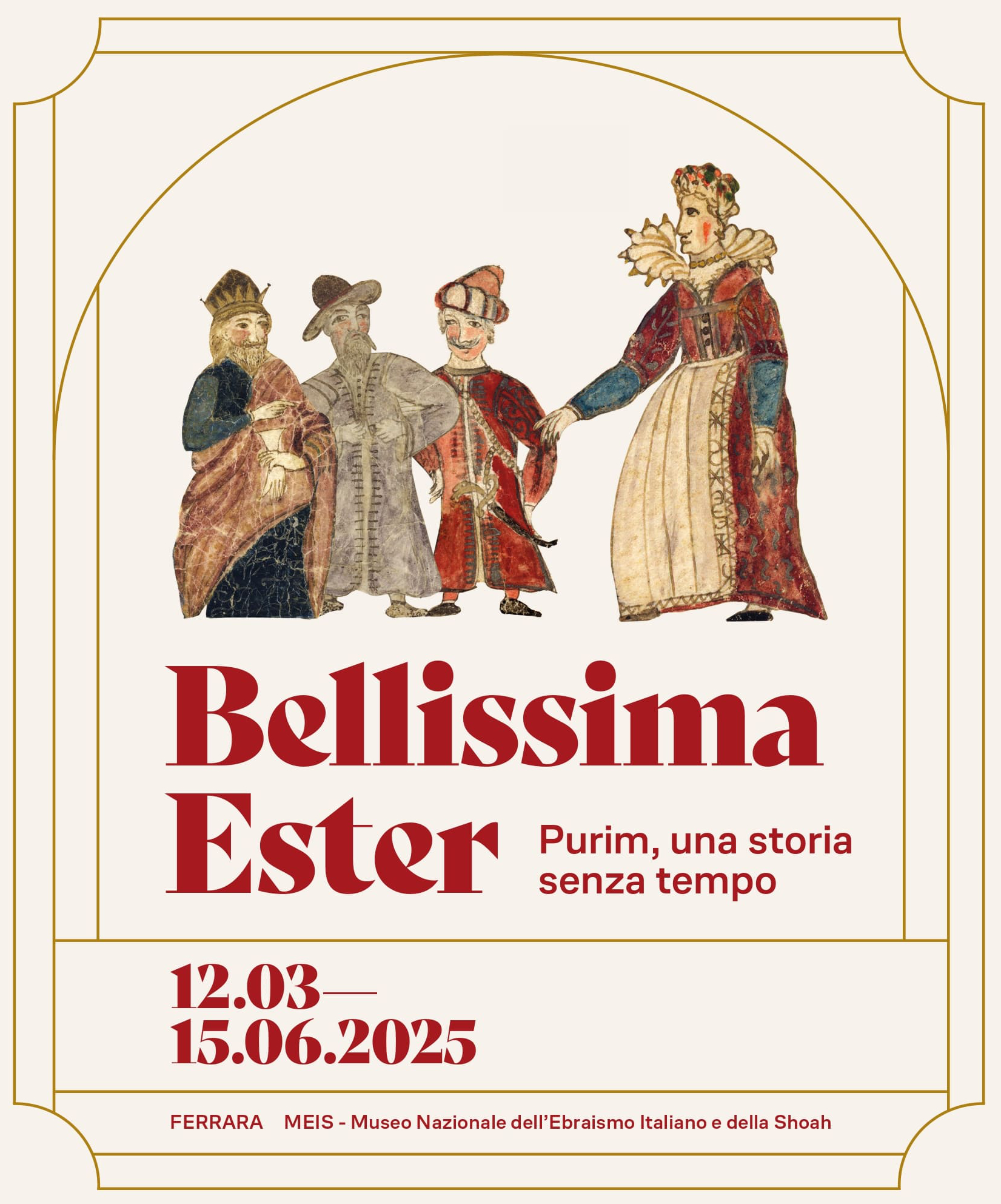

Prorogata fino al 20 luglio la mostra del MEIS “Bellissima Ester”

Online event

Sabato 24 maggio, appuntamento in giardino con la Biblioteca del MEIS