Prison No More

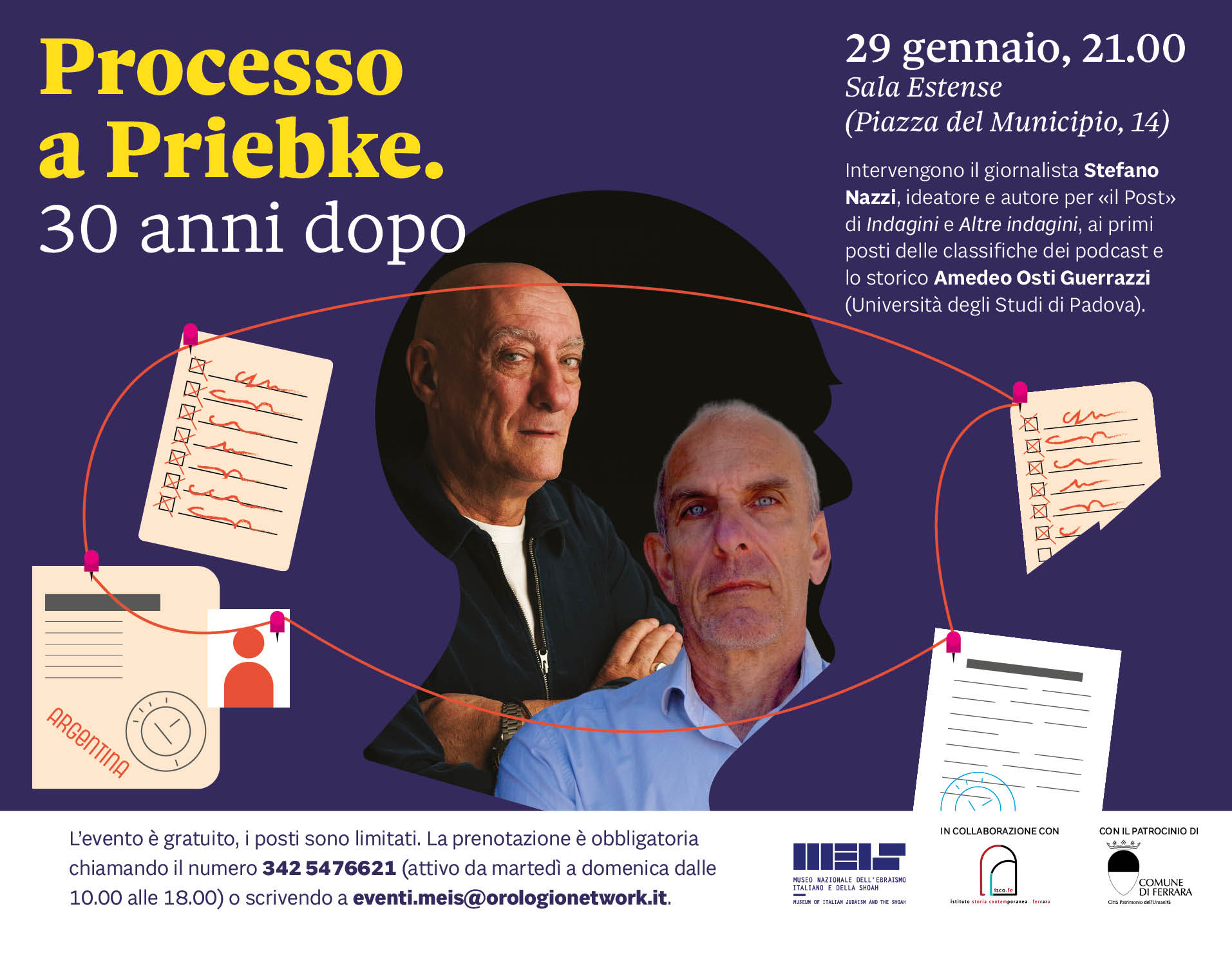

In 1912, a two-story brick prison was inaugurated in Ferrara, a city in Italy’s Emilia Romagna region. Over its 80 years of operation, until it was closed in 1992, this was a bleak spot in the beautiful city. Among its detainees were Jews during the Fascist period. But two months ago, Ferrara saw a key step in the profound transformation of this location: On Dec. 13, 2017, the first day of Hanukkah, Italy’s National Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah opened in the old prison. This is the initial phase of a monumental project – known as MEIS, after its initials in Italian – to be completed in 2020, with additional buildings that will create a major Jewish cultural hub.

The inaugural event was standing room only, bustling with news camera crews, international journalists, Ferrara residents, and Italian dignitaries, including President Sergio Mattarella. Curators and staff were ceremoniously thanked and acknowledged for their collaborative work to finally bring MEIS to the public. And the mission of MEIS is ambitious: to raise awareness of the vibrant 2,200 years of Italian Judaism, promoting dialogues on the topics of minorities, and of how different cultures interact through history.

In the words of the museum’s president, Dario Disegni, “Ferrara’s former prison, a place of segregation and exclusion, has become a place of inclusion.” Ferrara native Dario Franceschini, Italy’s minister of culture, called the opening “an important step forward, a dream achieved.”

The dream began in 2003 with an Act of Parliament, where all parties unanimously voted to support the initiative. What began as a plan for a Holocaust museum expanded in 2006 to a bigger project: to establish a museum to tell the story of two millennia of the Jewish experience in Italy. “The fact that this is a national project is what makes this museum unique in the world,” said MEIS Director Simonetta Della Seta. And unlike smaller, locally funded Jewish museums in Italy, this one is entirely funded, to the tune of 47 million euros, by the Italian government.

In 2011, Studio Arco of Bologna and SCAPE Sp.A Rome won an international competition to design the project. The team, comprising Italian, Japanese, and American architects, created a plan to retain and renovate two of the original Ferrara prison buildings, and to regenerate the property, opening it up in a light-filled, contemporary style to blend with the city.

Construction of five modern buildings, inspired by the five books of the Torah, will begin this year. These buildings will complete the cultural complex of free public spaces, an auditorium, museum shop, library, archives, educational suites, gardens, and restaurants. Work on the grounds was ongoing during the December opening, adding an energetic pulse, and a model of the completed project was displayed.

The museum’s current offerings comprise two parts. First a 24-minute immersive video, “Through the Eyes of the Italian Jews,” which takes viewers time-traveling through the entire history of Italian Judaism, using different narrative voices to personalize key experiences—from a Jewish man deported to Rome after the destruction of the Jerusalem temple to a scribe in the middle ages and a young girl expelled from school in 1938 because of racial laws. The video defines the MEIS vision: to tell the complicated story of the Jewish experience in Italy, which includes painful periods as well as times of peace and collaboration. Second is a 10,000-square-foot exhibit, filling two floors: “Jews, an Italian Story: The First Thousand Years.” Here large video images, texts from historical writers and curators, and over 200 objects from museums around the world—ancient coins, medieval manuscripts, amulets—present the integrative relationship between Jews and a Christian majority, a beneficial interchange that never involved assimilation or loss of identity.

“We are telling you a story of Italian Judaism through the objects of people who lived it,” said guide and curator Sharon Reichel, as she led guests through the exhibit. “It is a new way of telling the story in a Jewish museum. We are presenting a dialogue between a minority and majority, and that’s what makes this Italian story, that’s never been told this way before, so enriching.”

The exhibit, which will be open until Sept. 16, includes a reproduction of a relief from the Arc of Titus, commemorating Rome’s victory over the Jews in 70 CE. This is a landmark of the Jewish presence in Rome, a presence that has endured uninterrupted to the present day, making it the oldest Jewish community in the Western world. Jewish culture took root and flourished throughout the peninsula in the seventh to 11th centuries, as shown through synagogue mosaics, oil lamps inscribed with menorahs, catacomb frescos, and richly decorated manuscripts.

Much of the contents of “The First Thousand Years” will be retained for the final museum. And in the next couple years, exhibits focusing on the Jews in the Italian Renaissance and then the Shoah will be rolled out, a process that will complete the museum in stages for its 2020 opening. Opening one exhibit at a time, in the words of curator Danielle Jalla, “offers a rare opportunity to test out how the permanent exhibit could shape up, a sort of dress rehearsal before an audience.”

Ferrara was chosen as the location for MEIS because of its long history of active Judaism, documented back to Roman times. The high point of Jewish history in Ferrara came during the reign of the Estes in the 15th and 16th centuries, when the dukes opened the city to Jews who were expelled from Spain, Portugal, Germany, and Italy’s papal states, offering them freedom and protection. Jews thrived here during the Renaissance, working as money lenders, engineers, doctors, and in publishing. By 1589, 2,000 Jews lived in Ferrara, forming a community in what is now the historic center on Via Mazzini, Via Vignatagliata, and Via Vittoria.

But after the Este reign, Jews’ fortunes fell. In 1627, the Ferrara ghetto was introduced, mandating that Jews lived enclosed in its five gates until it was abolished when the Kingdom of Italy was formed in 1859. Liberation opened a period of renewed prosperity for the Ferrara Jews. They fought in WWI and integrated into the city politically: A Jewish mayor, Renzo Ravenna, governed from 1930 until 1938 when Fascist race laws began to be enforced. As WWII began, many of the 700 Jews living in Ferrara escaped. One hundred died in the Holocaust. When the war was over, only 150 returned.

At the museum’s opening, Andrea Pesaro, president of Ferrara’s 100-member Jewish Community, spoke to journalists about Judaism in Ferrara. Despite its small size, he said, the city’s Orthodox community carries on with services at their synagogue on Via Mazzini, which has been in continuous operation since the 15th century.

At 80, Pesaro joked that he brings the average age of the current Jewish community down. All are looking forward to the changes that MEIS will bring—hopefully an influx of new young people, perhaps not only from Italy but also Jews from other parts of the world who are passionate about the project and will revitalize the dwindling population. Inspired by the MEIS opening, the Ferrara tourist board is creating Jewish tourist itineraries for visitors, erecting signage throughout the former ghetto, offering guided tours, and creating a pedestrian path from the synagogue to the museum.

“MEIS will offer a cultural and tourism opportunity on an international scale,” said Franceschini, the culture minister, “just as the city deserves.”

Altri contenuti

4 marzo 2026: 110 anni dalla nascita di Giorgio Bassani

12 marzo, evento online

8 marzo, incontro su Giorgio Bassani

12 febbraio, evento online