Jewish Italian Partisans, Young Resistance Fighters

They were youths, some studying at university, others still at their school desks. They were interested in love letters, writing short stories, going out with friends. In 1938, with the enactment of the racial laws, they were alienated from society, expelled from the universities and schools, and excluded from public life.

These young people had just seen all their rights denied, and could read bewilderment, confusion, indecision in their parents’ eyes.

Thus these youngsters — Italians, Jews, persecuted, hopelessly adrift — would join others and fight to regain their freedom and to free their entire country. They brought their families to safety and exposed themselves to the two-fold danger of being both Jewish and anti-fascist.

They moved into the mountains, slept in uncomfortable, makeshift shelters, were sent into exile or captured.

So many Italian Jews, both women and men, joined the Resistance, contributing to the liberation of Italy.

The National Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah wishes to share ten stories of courage, idealism and selflessness. The pursuit of freedom is a challenge to be fought for day in and day out, and should be paid homage to every day, let us remember those youths in the mountains who made our world better.

“In a situation as dramatic as the one we are now living through,” writes MEIS President Dario Disegni, “this 25th of April, Italian Liberation Day, must demand of us a great moral and civil recovery, prompting us to reflect not only on the horrors of the past, but also on the profound injustices and inequalities still present in our society. In celebrating Liberation Day and recalling those who fell for our freedom — including Emanuele Artom and many Jewish partisans — such recovery will help us emerge from the current crisis that has engulfed the entire planet more humane, more upright, more united and determined to build a fairer, more equitable, more livable world: in sum, a place better than the one we have been living in”.

We thank the Center of Contemporary Jewish Documentation-CDEC

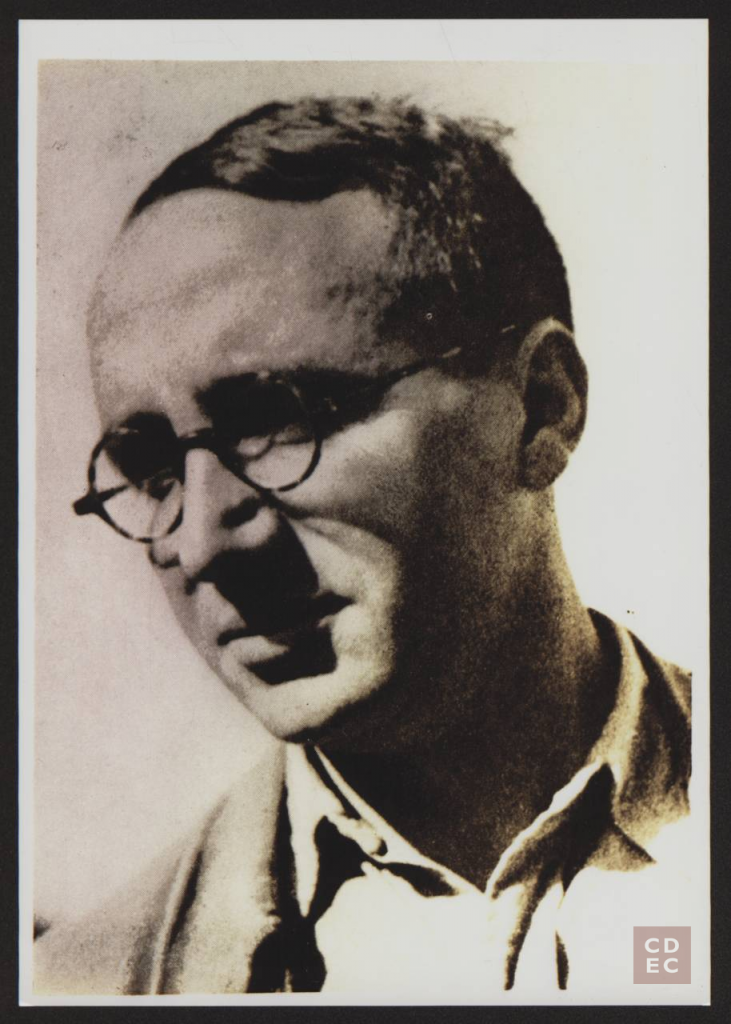

Emanuele Artom, diary of a partisan

Born in Aosta in 1915 to a family from Turin, Emanuele Artom grew up in the Piedmont regional capital and studied under Augusto Monti at the Massimo D’Azeglio Classical Lyceum. He enrolled in the Faculty of Letters, graduating with honors in 1937.

With his brother Ennio, who died tragically in a mountain accident, he was leader of a Jewish cultural club which counted Primo Levi, Franco Momigliano and Luciana Nissim, among its members.

In 1943 he joined the Partito d’Azione and, as partisan, took the name of Eugenio Ansaldi. Always on the front lines and engaged in complex, dangerous activities, he was a political commissioner.

Captured in 1944, he was brutally tortured and died in jail from the abuses he suffered.

His diary — published unedited by Bollati Boringhieri under the title “Diario di un partigiano ebreo” (edited by Guri Schwarz) — is considered not only a valuable historical tool but has also been praised for its literary value.

Emanuele’s mother, Amalia, who held a degree in Mathematics, was the longtime principal of the Jewish secondary school in Turin that bears his name.

Photo credit: Giuseppe Mosso, Ritratto di Emanuele Artom, 1935 ca. Archivio CDEC, Fondo Antifascisti e partigiani ebrei in Italia 1922-1945

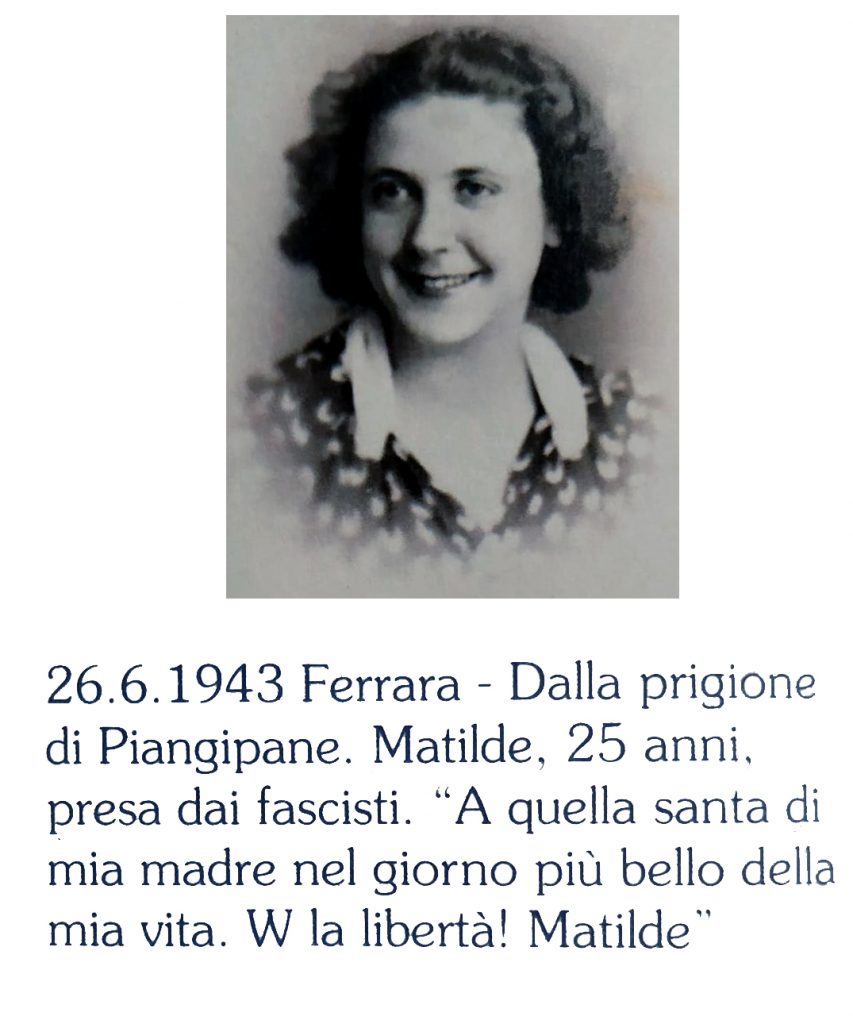

Matilde Bassani Finzi and the school in via Vignatagliata

Born in Ferrara in 1918, from an early age, Matilde Bassani was raised on ideals and politics. Her father, a professor of German at the Technical Institute, was fired in the 1920s for his anti-fascist ideals; her uncle, Professor Ludovico Limentanti, signed the Manifesto of the Anti-Fascist Intellectuals and her cousin was the physicist and partisan Eugenio Curiel.

Her professor, Francesco Viviani (also the teacher of the writer Giorgio Bassani) who died in Buchenwald, and the socialist teacher Alda Costa both played an important role in her education.

Having graduated with honors in Literature, together with Giorgio Bassani and Primo Lampronti, Matilde was one of the teachers at the Jewish school in Via Vignatagliata, which welcomed the children expelled from public institutions in Ferrara.

The school in Via Vignatagliata was top notch. In addition to the immortals of Italian literature, the children also studied contemporary poets; it was here that the ideals of freedom and equality were imparted.

In 1943 she was arrested for her anti-fascist activities and taken to the prisons in Via Piangipane (now home to MEIS). Released in July of the same year, she fled to Rome and met her future husband Ulisse Finzi, with whom she shared the decision to resist.

After the war, she made a name for herself as a psychologist and always remained on the front lines, defending rights and holding prestigious positions in the Unione Femminile Nazionale [National Women’s League] and the Consiglio Nazionale delle Donne Italiane [National Council of Italian Women].

When interviewed by Anna Quarzi, President of the Istituto di Storia Contemporanea, in 1997, she said: “From an early age, I was nurtured on milk and anti-fascism. In fact, my family was anti-fascist out of a natural aversion to dictatorships, out of a love for freedom”.

Photo credit: Archivio storico e fotografico della famiglia Finzi – Milano

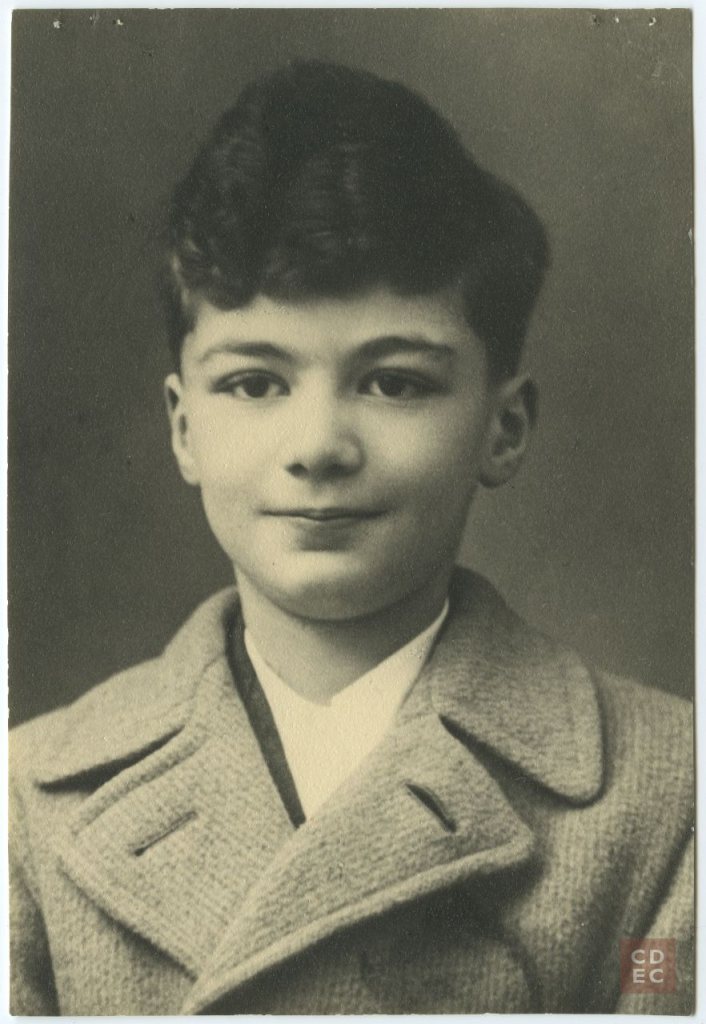

Franco Cesana, a soldier at 13 anni

Born in Mantua in 1931, Franco Cesana is often remembered as the youngest partisan to fall in the Italian Resistance. He grew up in Bologna, was expelled from public school after the promulgation of racial laws and was admitted to the Orphanage “Orfanotrofio Israelitico di Torino e di Roma”.

Following in the footsteps of his brother Lelio, declaring he was of age, he joined the Brigate Garibaldi before he was thirteen. Near Pescarola, on the outskirts of Bologna, he and his brother were taken by surprise by enemy fire, Lelio managed to save himself, Franco did not. There is a touching letter he wrote to his mother in which he reassures her about his condition: “So you don’t have to worry about me, I’m fine. My health is very good; sleeping is just a bit precarious”.

The story of Franco Cesana was told in the exhibition “Stars without a heaven. Children in the Holocaust” produced by Yad Vashem of Jerusalem and MEIS in cooperation with the CDEC and the Legislative Assembly of the Emilia-Romagna Region.

Photo credit: Anonimo, Ritratto di Franco Cesana, 1940 ca. Archivio CDEC, Fondo Antifascisti e partigiani ebrei in Italia 1922-1945

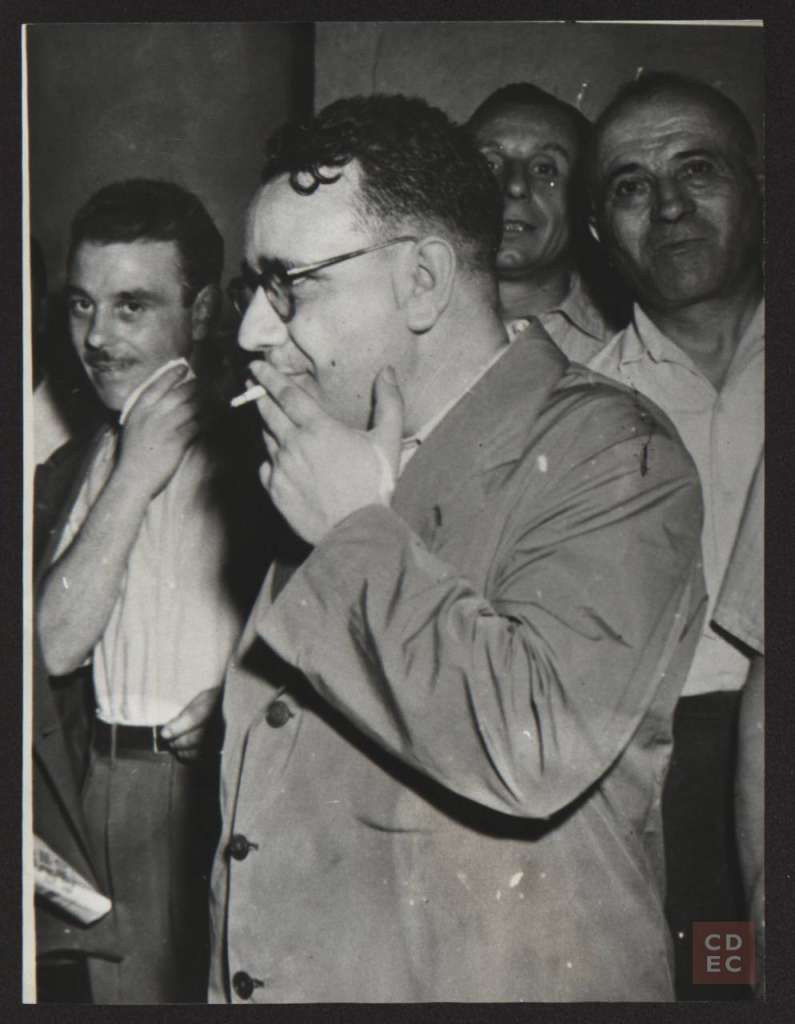

Eugenio Curiel, the physicist of the Resistance

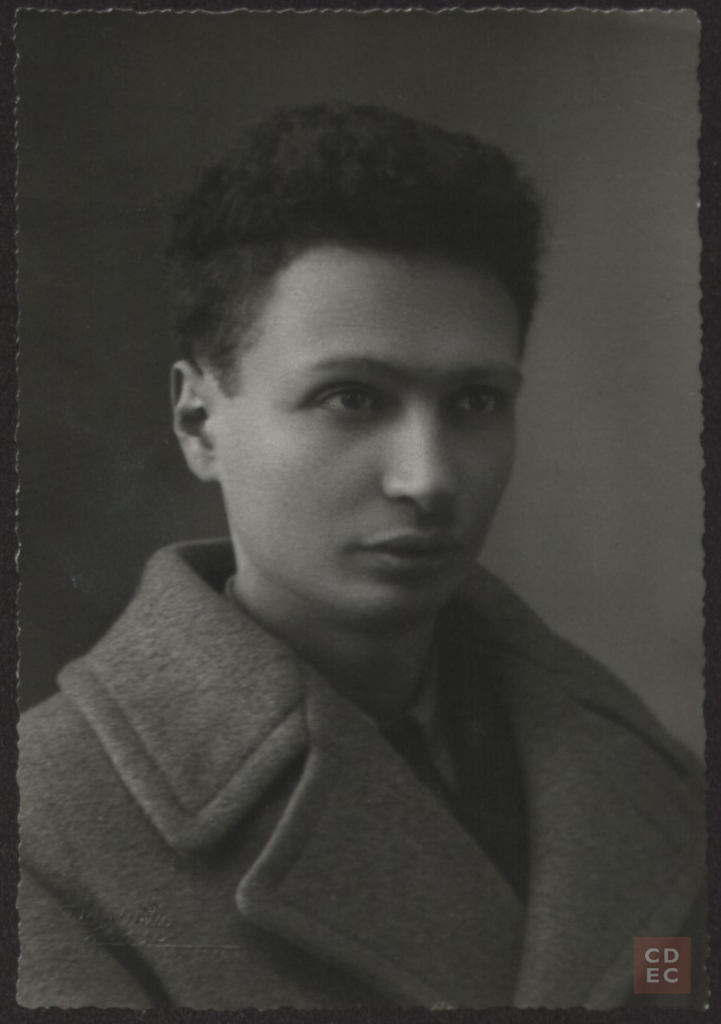

Born in Trieste in 1912 into a well-educated, well-to-do Jewish family, Eugenio Curiel distinguished himself through his political commitment, always strongly linked to his intellectual training.

After studying engineering for two years at the University of Florence and transferring to the Polytechnical Institute of Milan, he decided to enter the Department of Physics at the University of Florence where his uncle, Ludovico Limentani, was professor of moral philosophy. His brilliant career was marked by periods during which he taught in the schools, until he was hired by the University of Padua as an assistant.

Within the university environment, Curiel forged bonds of friendship and took steps toward Communist-inspired political activism.

Dismissed from teaching after enactment of the racial laws, he began to move between Italy and Switzerland. He was wanted for his anti-fascist activities and was arrested in Trieste in 1939. Condemned to exile, he moved to the island of Ventotene. With the fall of Fascism, Curiel returned to Milan to resume his political activities. However, on 24th February 1945, he was recognized by the Brigate Nere and, after being chased, he was shot dead.

He was awarded the Medaglia d’Oro al Valor Militare [Gold Medal of Military Valor] posthumously.

Photo credit: Anonimo, Ritratto di Eugenio Curiel, 1935-1940 ca. Archivio CDEC, Fondo Antifascisti e partigiani ebrei in Italia 1922-1945, b. 5, fasc. 99

Mosè Di Segni, the free doctor

Doctor, anti-fascist, Zionist, partisan.

The soul of Mosè Di Segni, born in 1903 in Rome and died in 1969, has many facets. Father of three children, Elio, Frida and Riccardo (today the Chief Rabbi of the Jewish Community in Rome), Mosè Di Segni was a pediatrician in Florence and leader of the Avodà Zionist Club founded by Enzo Sereni.

In 1936 he was sent as military physician to Spain but two years later, due to the racial laws, he was discharged from the army and fired from the Spallanzani hospital in Rome where he had worked.

An advisor to the Jewish community, he was actively engaged in helping the Roman Jews in their darkest years. Warned by a friend that he was on a list of people destined for deportation, he managed to hide in Serripola (San Severino Marche) where he joined the Brigate Garibaldi as a partisan, never failing in his vocation as a doctor and always helping the local population.

Precisely for this reason, a few years ago the Municipality of San Severino delle Marche granted his three children honorary citizenship.

Recently the book “Mosè Di Segni medico partigiano. Memorie di un protagonista della Guerra di Liberazione (1943-1944)”, edited by Luca Maria Cristini (San Severino Marche, Edizioni della Riserva naturale regionale del Monte San Vicino e del Monte Canfaito, 2011) was published.

Liana Millu, the writer from Birkenau

Liana Millu (Millul) was born in Pisa in 1914 and developed her passion for writing and journalism early on, writing for the Leghorn-based “Il Telegrafo”. After obtaining a master’s degree, she started teaching school but, the following year, was fired because of the racial laws. She moved to Genoa and continued writing until the September 8, 1943 when she decided to join the clandestine partisan group “Otto”. After being denounced by an informer, she was arrested in Venice on March 7, 1944, taken to the Fossoli camp and, from there, deported to Auschwitz and transferred to Ravensbrück. In 1947, two years after the end of the war, she published “Smoke Over Birkenau”, one of the very first memoirs dedicated to the Holocaust: a very important testimony revolving around the experiences of women in the camps, as recalled by Primo Levi who wrote the introduction to the 1971 edition. Immediately after the liberation, Liana started writing the book in pencil and gave the stub to Levi himself, a sort of passing of the baton. She died in Genoa in 2005.

In this video (in Italian) produced by Fondazione Fossoli, Piero Stefani and Ottavia Piccolo talk about the personality of Liana, through memories and readings of her works.

Photo credit: Anonimo, Ritratto di Liana Millul, 1940 – marzo 1944 Archivio CDEC, Fondo fotografico Millu Liana

Luciana Nissim, Primo Levi’s friend

Born in Turin in 1919, and despite the racial laws, Luciana Nissim managed to graduate with honors, receiving a degree in medicine in 1943.

She came into contact with Primo Levi and became his friend. After the armistice, she decided to join him in the partisan struggle, reaching the Giustizia e Libertà group of freedom fighters in Valle d’Aosta. On December 13, 1943, she was arrested with her companions and taken first to the Aosta prison and then to the Fossoli camp. From there, in February 1944, she was deported to Auschwitz where she managed to save herself because she was a doctor.

After the war she was reunited with her family, specialized in pediatrics and married Franco Momigliano, also a partisan. She began working in Milan with the great psychoanalyst Cesare Musatti, making a name for herself in the Italian Psychoanalytic Society and introducing great innovations in methodology.

Her story and writings are collected in the book “Ricordi della casa dei morti e altri scritti” published by Giuntina. She died in Milan in 1998.

Photo credit: Anonimo, Ritratto di Luciana Nissim (a sinistra) e Vanda Maestro (a destra), 1940 ca. Archivio CDEC, Fondo fotografico Maestro Vanda

Rita Rosani, teacher, holder of a Medaglia d’oro

The partisan Rita Rosani, winner of a Medaglia d’Oro al Valor Militare [Gold Medal of Military Valor] was born in Trieste in 1920 to a Jewish family of Moravian origin.

The original family surname, later Italianized, was in fact Rosenzweig (“rose branch”).

She was a primary school teacher at the Jewish school and engaged to Giacomo Nagler, known as Kubi, who would meet his fate in Auschwitz.

After having saved her family from deportation by hiding them away in Friuli, she joined the Resistance, first in Portogruaro and then in Verona. She formed the “Aquila” band and fought in the Valpolicella and Zevio areas. She was captured on Mount Comun and killed by a lieutenant of the Republican National Guard on September 17, 1944. This is the motivation for posthumously granting her the Medaglia d’Oro: “Politically persecuted, she joined a band of armed partisans, living the hard life of a fighter. She was a companion, sister, leader of indomitable valor and ardent faith. She avoided the certain dangers and suffering of the rugged existence to carry out the delicate, highly risky missions assigned to her”.

It is a tribute to her that Livio Isaak Sirovich wrote the book “Non era una donna, era un bandito . Rita Rosani, una ragazza in guerra” (Cierre Edizioni).

Photo credit: Archivio Fondazione CDEC, fondo Antifascisti e partigiani ebrei, b. 16, fasc. 353.

Enzo e Emilio Sereni, a story of two brothers

Born in 1905 in Rome to an upper middle-class family (his father was physician to the Kings of Italy), from a very young age Enzo Sereni was passionate about the Zionist movement and ideals. After receiving a degree in Philosophy at the age of 22, he made his aliyah (literally “ascent”), emigrating to the Mandate for Palestine where he started working and building the Givat Brenner kibbutz.

Socialist and pacifist, Sereni wrote essays and did translations, becoming a true cultural point of reference. When the cloud of Nazism approached Europe, he took over the task of helping the persecuted Jews emigrate and was temporarily arrested by the Gestapo.

He helped organize the SOE, the British Special Operations Executive parachute units and created a special section of the Jewish Agency aimed at saving European Jews from Nazi persecution. In 1944, at over forty years of age, he was parachuted into Northern Italy where he took the name Samuel Barda, but was captured shortly thereafter and deported to Dachau where he was assassinated.

On Mount Herzl in Jerusalem, also known as Har Hazikaron, the Mount of Remembrance, a plaque celebrates his courage.

To learn more about his story, the book: “The Emissary: A Life of Enzo Sereni” by Ruth Bondy (Robson Books).

His brother Emilio Sereni, born in 1907, received a degree in Agronomy and joined the Communist Party at the age of twenty. Active in politics, he made many trips including one to Paris in 1930 where he came into contact with Palmiro Togliatti. Returning to Italy he was sentenced to prison but, after being pardoned, he managed to return to France where he continued his anti-fascist operations. Convicted again in 1943, he managed to escape and settle in Milan, taking over the office of demonstrations and propaganda. He served as party representative at the Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale Alta Italia [National Liberation Committee for Northern Italy] in Milan. Once the war was over, he held the roles of Minister of Post-War Social Services, Minister of Public Works and Senator. His studies on the condition of the Italian countryside and agricultural issues are fundamental works.

The extraordinary events of this Italian Jewish family are preserved and recounted in the historical novel by Clara Sereni (Emilio’s daughter) “Il gioco dei regni” (published by Giunti).

Photo credits: Anonimo, Ritratto di Enzo Sereni, 1940 ca. Archivio CDEC, Fondo antifascisti e partigiani ebrei in Italia 1922-1945, b. 18, fasc. 400

Anonimo, Ritratto di Emilio Sereni, 1945-1950 ca. Archivio CDEC, Fondo antifascisti e partigiani ebrei in Italia 1922-1945, b. 17, fasc. 399

Other news

Online event, March 12

Online event – February, 12

Online event, Corresponding Art

November 26, online event